What is the current offer in social certifications and how will it develop?

Social issues across global supply chains have received more attention over the past years. Social certification standards serve as a tool to ensure good social practices. Through certification, you can show your buyers and end-consumers that you comply with sustainability requirements. There are many different certification schemes out there, each with their own scope and focus. This makes it very important to know which standard is relevant for what product, market and segment. It will help you make the right decisions when choosing a specific standard and may increase your access to European market access.

This study provides an overview of the social certifications that are relevant for food and non-food sectors and that are currently in demand on the European market. Along with definitions, origin and trends, this study identifies the main certification standards used in Europe and their main differences. Moreover, it helps you choose the best certifciation for your company by highlighting possible benefits and hurdles to certification and providing a model to choose a certification standard to fit your needs.

Contents of this page

- What are social certification standards?

- What is the origin of social certification standards?

- What are the developments and trends in social certification standards?

- What are the most demanded social certification standards in Europe?

- What are the main differences between the most demanded social certification standards?

- What are possible benefits of social certification standards?

- What are hurdles related to social certification standards?

- How to choose the certification standard that fits your needs best?

1. What are social certification standards?

There are currently over 400 voluntary sustainability standards out there. These can relate to environmental, social and/or economic aspects of sustainability. Social standards specifically deal with social issues like fair wages, working conditions, labour rights, health and safety, fair prices, and gender equality.

Product certification vs. social compliance standards

Some standards specifically focus on product certification. Product certification guarantees that a product has been produced, processed, and traded according to the social and/or environmental criteria of a specific standard. Examples of product certification schemes include Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance, FairWild and Fair for Life. A certification label is often used on final consumer products.

Social compliance on the other hand, refers to how a business protects the health, rights and safety of its staff, supply and value chain. These social compliance systems provide companies with guidelines to report on their social performance. Examples of these are Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI), SMETA (Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit) and Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI). Several of these social compliance standards can be certified; such as SA8000, B-Corporation, Worldwide Responsible Accredited Production (WRAP) and For Life.

Social certification does not say anything about the quality of a product. Certified products are found both on the mainstream and specialty markets. Due to stricter sustainability legislation in Europe, certification on the mainstream market is increasingly used as an entry requirement by large-scale retailers and importers. In niche markets, certification plays a different role. Sometimes, (social) certification is even seen as counter-productive, as supply chains dealing with high-quality and exclusive products may already contain many sustainability practices that go beyond the standards of certification schemes.

Figure 1: Examples of product certifications including social criteria

Source: ProFound, 2022 (logos retrieved from certification websites)

Figure 2: Examples of social compliance standards/certifications

Source: ProFound, 2022 (logos retrieved from standard websites)

Company X produces wild-collected herbs, vanilla and tea. They can choose to use product certification standards, such as FairWild for their wild-collected herbs and Rainforest Alliance for their tea production, leaving their vanilla uncertified. They can also certify their business with SA8000, proving their commitment to social accountability and to treating their employees ethically and in compliance with global standards.

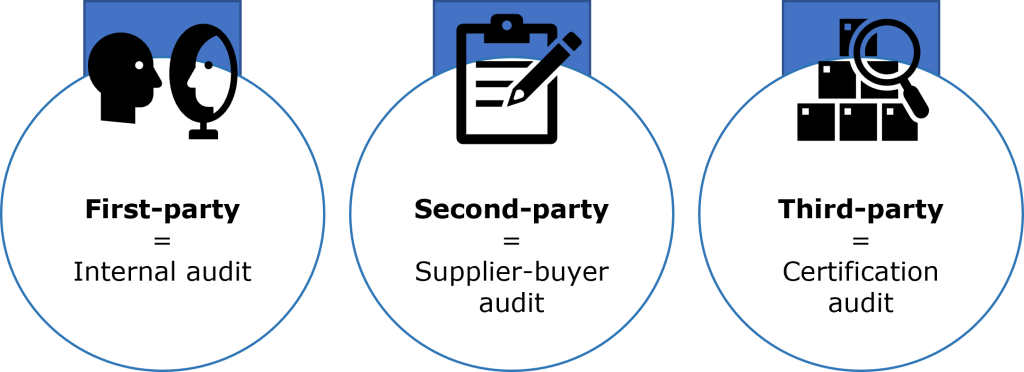

First, second and third-party audits

Standards will vary in content, scope and how they are audited. There are first-party, second-party and third-party audits. A first-party audit or self-verification is an internal control done by a company itself. In a second-party audit a buyer verifies whether a supplier complies with the criteria of a specific standard. A popular second-party social compliance standard among European buyers is the Ethical Trading Initiative.

A second-party audit often refers to a supplier questionnaire. European buyers will require their suppliers to fill out their own supplier questionnaires, through which a buyer ensures that their suppliers meet certain values for social responsibility. The questionnaires provide a documented record of statements made by suppliers on a wide range of topics about the company, its products and its standards. As compliance with legal requirements becomes more complicated, these questionnaires become longer. Along with information on type and origin of ingredients and how these are produced, these often include statements on labour and environmental policies and practices as well.

A third-party audit involves the control of an independent entity: a certification body. This entity will check whether a supplier and/or buyer meets the standards of a specific certification scheme. The certification body provides a certificate as proof when all requirements are met. This means that certification is always done by a third party. Controls by an independent third party are seen as more credible and reliable than self-verification.

Figure 3: First, second, and third-party audits

Source: ProFound, 2022

Corporate sustainability codes of conduct

Many European buyers will have at least one certification scheme in their portfolio. In addition, many larger-scale companies have developed their own sustainability plans over the years. Some of these companies commit to the use of the previously mentioned third-party certification standards, some have developed their own private sustainability programmes, while others combine both approaches.

There are numerous reasons for companies to decide to bypass independent third-party certification standards. For instance, there may be a lack of trust that premiums of these standards reach farmers’ organisations. Another reason might be to increase possibilities for compliance at a lower cost without increasing supply risks.

If a buyer only works with their own sustainability standards, the company will most likely perform its own audits. Large companies, however, may also hire certification bodies to verify compliance to specific corporate sustainability standards. Examples of such certification bodies include Kiwa, SGS, and Control Union. In all cases, companies will propose their sustainability programmes/standards to producers and exporters to be qualified as a supplier. This means that suppliers need to be able to meet these requirements to be able to do business with these companies.

Examples of these private corporate sustainability programmes/standards are:

- Cocoa: Cocoa Life by Mondelez

- Coffee: Coffee and Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E.) Practices by Starbucks

- Botanicals: Mabagrown by MartinBauer

- Various sectors: Sustainable Agriculture Code by Unilever

- Apparel: Sustainability Commitment by H&M

These programmes often include private labels which are being displayed on final consumer products.

Tips:

- Consult our social certification matrix for an overview of available social certifications as demanded in Europe.

- Consult the International Trade Centre (ITC) Standards Map for an overview of different certification schemes.

- Learn more about organic certification on the website of the European Commission. Note that the production, distribution and marketing of organic goods is rooted in European legislation.

2. What is the origin of social certification standards?

The development and growth of the fair trade movement has mostly been associated with development aid and solidarity trade, as a response to poverty and disasters in the global South. The origin of social certification standards can be traced back to the 1940s and 1950s when the first fair trade shops and companies were set up in Europe and North America. In the 1960s and 1970s, various international NGOs started advocating for fair marketing organisations that would support disadvantaged producers in Latin America, Africa and Asia.

The goal was to create greater equity in international trade. Developing countries were also addressing international political fora at this time to spread the message “Trade not Aid”, emphasising equitable trade relations with the global South. These developments led to the establishment of the first labels and standards in the 1980s.

As globalisation took hold in the 1990s, social issues became more prominent. While leading to new jobs and growth, expanding international value chains stretched across continents which also increased social inequality. Public awareness of these developments increased through publicised NGO movements, such as the campaign against Nike for worker abuse and exploitation and documentaries on child labour on cocoa plantations.

The 2000s marked a rapid growth of sustainability standards as public concern about climate change and social inequalities increased. Global frameworks such as the Millennium Development Goals and UN Global Compact Principles were launched. Existing standards were more widely adopted by companies and new ones established, such as UTZ (2002) and Fair for Life (2006).

Also, environmental and social standards have converged more over the years. An example of this is the FiBL certification programme WeCare. This standard encompasses both environmental and corporate social responsibility criteria. Another example is Naturland Fair, which unites organic agriculture with social responsibility and fair trade principles.

Initially, the movement focused on marketing craft products, and it expanded to food products in the 1970s, starting with coffee and tea. Over recent decades, standards evolved greatly in terms of sectoral and topical coverage, going from an original focus on agriculture, forestry and fair trade in the early nineties to a broad range of issues and sectors nowadays.

Table 1: Important milestones in development of social certification standards

| 1968 | The slogan “Trade not Aid” gained international recognition |

| 1973 | First fairly traded coffee imported to the Netherlands from Guatemala |

| 1988 | First Fairtrade label is established along with the Max Havelaar Foundation in the Netherlands, when Mexican coffee farmers indicated that they would prefer a fair price for their coffee over charitable support. This label expanded into other European countries |

| 1989 | World Fair Trade Organisation created |

| 1989 | Rainforest Alliance created |

| 1997 | Several national Max Havelaar Foundations merged into Fairtrade International, raising awareness about the challenges of farmers in developing countries |

| 2003-2004 | Multinationals announce compliance with one or more sustainability standards |

| 2010 | Over 400 sustainability standards established, compared to less than 200 ten years earlier |

Tips:

- Consult the website of ISEAL Alliance; it offers insight into the most recent studies of the impact on and evaluation of certification.

- Refer to the website of the United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards (UNFSS). The website contains lots of information, analysis, and discussions on sustainability certification standards.

3. What are the developments and trends in social certification standards?

Social compliance audits and product certification are crucial for European buyers, as well as for exporters to meet buyer demand. Their importance is likely going to increase due to new due diligence laws, as well as increased consumer demand for transparency and traceability. As sustainability concerns change, standards look for ways to adopt, while buyers might look for ways to go beyond certification to ensure ethical and fair trading practices.

National and sector-wide sustainability initiatives drive up certification

Due to growing sustainability concerns across Europe, a growing number of initiatives aim to increase farming profitability, improve livelihoods and well-being, and conserve nature. There are initiatives on national levels as well as global sector-wide initiatives.

What all initiatives have in common is that they provide a platform for supply chain actors to share experiences and to create a common understanding of the sustainability issues affecting them. The focus on and importance of sustainability for companies active in any sector will only increase and intensify, broadening the sustainability focus to include issues such as living income.

Sector-wide sustainability initiatives

Examples of multi-stakeholder, sector-wide initiatives are:

- Coffee: The Global Coffee Platform (GCP) is a multi-stakeholder membership association of coffee producers, traders, roasters, retailers, sustainability standards and civil society, governments and donors, united under a common vision to work collectively towards a thriving, sustainable coffee sector for generations to come.

- Spices: The Sustainable Spice Initiative (SSI) aims to sustainably transform the mainstream spices sector, securing future sourcing and stimulating economic growth in producing countries. The consortium consists of an international group of companies active within the spices and herbs sector, and NGOs.

- Nuts: The Sustainable Nut Initiative (SNI) aims to improve the circumstances in nut producing countries, while working towards sustainable supply chains. Members of SNI include largescale retailers, traders and processors.

- Cotton: The Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) aims to help cotton communities survive and thrive, while protecting and restoring the environment. BCI defines what a better, more sustainable way of growing cotton looks like, and trains and supports farmers to adapt to the corresponding techniques. BCI unites a whole range of industry stakeholders, from ginners and spinners to brand owners, civil society organisations and governments.

These initiatives partly drive demand for certification. For instance, members of SSI have committed to strive for a fully sustainable spice production and trade in the sector. One way for buyers to reach this goal is to increase their sourced volumes of certified products. SSI members consider the standards in the SSI basket as adequate to certify or verify the sustainable production of spices. SSI member organisation Euroma (from the Netherlands), for instance, developed a strategy to source and market Rainforest Alliance-certified black pepper for European consumers.

The coffee sector is a similar case. In a move to advance sector transparency and the purchase of sustainable coffee, the GCP recognised nine sustainability schemes that prove coffee is being sourced sustainably. Interesting is that, besides third-party standards like Fairtrade and 4C, a number of second-party verified corporate sustainability standards are also part of this list, such as Ecom's SMS Verified and Olam's AtSource Entry Verified. In 2020, the largest coffee importing retailers and roasters reported that 48% of coffee was purchased through sustainability schemes recognised by GCP, up from 36% in 2018.

Although certification is used to prove sustainability, it is not yet a perfect solution. SNI, for instance, aims to go beyond certification and create a risk-based approach to tackle sustainability issues at a sector level.

National sustainability initiatives

Examples of national multi-stakeholder initiatives are:

- Cocoa: The German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa, the Swiss Platform for Sustainable Cocoa, the Dutch Initiative for Sustainable Cocoa (DISCO), Belgium’s partnership Beyond Chocolate and the French Sustainable Cocoa Initiative. In 2021, these national sustainability platforms signed a Memorandum of Understanding to collaborate more closely and to enhance transparency. This was in context of various problems in the cocoa sector of West Africa, such as child labour and largescale deforestation.

- Apparel: The UK’s Textiles 2030, the German Partnership for Sustainable Textile and the Dutch Agreement on Sustainable Garments and Textile. These initiatives respond to various problems and scandals in the apparel sector, such as pollution, fast fashion and the 2013 collapse of a garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Member companies of these initiatives have adopted their practices to contribute to the targets set by the initiative and will increasingly continue to do so. For example, through the endorsement of specific certification schemes or codes of conduct.

Tips:

- Refer to our specific sector studies on the CBI website for more information on sustainability initiatives and developments in each sector.

- Consider becoming part of a sector-wide initiative relevant to you. This can make your company more competitive and more attractive to work with for European buyers.

- Have a look at the website of the Sustainable Trade Initiative, and get acquainted with their work. This Dutch social enterprise (foundation) aims for sustainable transformation of commodity supply chains, and is at the cradle of many sector-wide sustainability initiatives, among which: spices (SSI), nuts (SNI), vanilla (SVI), fresh fruit and vegetables (SIFAV).

- Investigate the existing sustainability standards established by retailers and other stakeholders in your specific sector. You may find these on the sustainability section of their website, or you can ask potential buyers. Assess whether you can adhere to the guidelines laid down by these standards. They can be a good starting point if you want to supply products to these companies.

Retailers’ own-label brands boost certification demand across Europe

Certification is increasingly used as a market entry requirement on the mainstream market of some sectors (example: coffee, cocoa and bananas). This is partly driven by increased commitments from retailers. Due to stricter sustainability protocols as a response to consumer demand for more product transparency, it is becoming more difficult for non-certified suppliers to access the European market. Note, however, that the overall market share of certified products in international trade is still rather small. These developments in the retail sector, however, provide an indication for continued importance and growth of the use of third-party certification.

Retailer commitments for third-party certification are strongest in their private-label products. These are gaining popularity and market share in Europe and are expected to continue to grow further. One of the drivers is that, in part because of the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers have smaller budgets to spend. Consumers will likely be more attracted to retailers’ private-label brands, as these offer similar characteristics and quality as branded products, at more affordable prices.

European markets with the highest private label shares in 2020 were Spain and Switzerland with nearly 50% of all products sold being retailers’ brands. The United Kingdom follows with a private label market share of 48%, followed by Portugal (45%), Belgium and Germany (both with 43% each).

Figure 4: Example of Fairtrade-certified own-label tea from Waitrose

Source: Waitrose

For instance, retailer Waitrose (UK) sells all their private label tea, coffee, sugar and cocoa in confectionery as 100% Fairtrade-certified since 2020. Coffee, cocoa, and rice sold under the private label brands of retailer Coop (Switzerland) is also fully Fairtrade-certified. Retailer Lidl (Germany), with shops all over Europe, also commits to fully certified products: 100% of products is certified to the RSPO Palm Oil standard. Moreover, all cocoa, tea and coffee used in their private label products are certified to Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance/UTZ and/or organic standards, and all chilled and frozen fish products under their private label is certified as MSC or ASC.

Tips:

- Be aware that, for some products, product certification has become a market entry requirement for Europe’s retail market. This is increasingly the case for tropical commodities like coffee, cocoa, palm oil, tea, forest products and wild-caught fish.

- Work together with other producers and exporters in your region if you lack company size or certified product volume. This may be interesting as retailers tend to source products of larger volumes and of consistent quality. Together, you can promote good-quality certified products from your region and be a more attractive and more competitive supplier for retailers (or other buyers) on the European market.

- Refer to retailers’ Codes of Conduct to see which sustainability elements they find important and what they require from their suppliers. For instance, check Ahold Delhaize’s Sustainable Retailing page or Carrefour’s (France) Corporate social responsibility page.

Social compliance audits crucial to comply with European legislation

Companies have long been encouraged to take responsibility of their supply chains on a voluntary basis. As results were not sufficient, some countries decided to introduce national mandatory due diligence laws for companies. Examples of this include the 2015 Modern Slavery Act of the United Kingdom, the French Duty of Care Act implemented in 2017 and the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Law of 2020. Germany passed the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act in 2021, which will come into force in 2023.

There has also been a broader push for mandatory due diligence legislation on a European level. These include new laws on human rights and environmental due diligence. These laws are currently being developed and are expected to come into force in 2023.

Companies subjected to these laws are obliged to report on their due diligence efforts. They will in turn require their suppliers to comply with stricter transparency requirements. European companies typically deal with this either through specific second-party supplier questionnaires or through third-party social compliance audits. Both are regarded a risk mitigation strategy, and especially audit reports are used as proof of good supplier performance.

However, it is argued that performing social compliance audits is not enough to prove this. Another worry is that suppliers now have extra costs and time investments to prove good practices, while they are also pressured to supply constant volumes of high-quality products on time and at low prices. Given the wide range of social compliance standards available (both from suppliers’ own codes of conduct and independent social compliance standards like BSCI and WRAP), suppliers often have to pay for and deal with various standards, depending on what buyers require.

Although social audits and certifications will likely continue to play an important role in dealing with current and new legislative requirements, specific companies are also looking for ways to go beyond certification (see section below).

Tips:

- Read more about the European Due Diligence Act on the CBI website.

- Learn how the Due Diligence Act is connected to the larger European Green Deal. This study on the CBI website sets out how the Green Deal requires that products sold on the European market increasingly need to meet higher sustainability standards.

- Consider developing and implementing your own policy on corporate social responsibility (CSR) or code of conduct. You can base this on the Base Code of ETI or on the standard guidelines as provided by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). A code of conduct is not always required by buyers but may be a good way to show potential buyers your views on social (and environmental) responsibility. This may help you to stand out when your buyer has to choose between several suppliers.

- Ensure that the farmers or suppliers you source from also have sustainable practices in place. Many social and environmental issues take place at farm/production level, which may not be a part of your direct handling and processing activities.

- Complete a self-assessment of a social compliance standard to become familiar with the requirements and prepare for the audit. For instance, refer to the producer self-assessment of BSCI or the self-assessment questionnaire of Sedex.

Companies search for ways to go beyond certification

Some brands and buyers in Europe, especially those active in niche segments, search for ways to go beyond certification. This might be a strategy to differentiate themselves on the market and/or a belief that certification on a stand-alone basis cannot address the challenges a company needs to deal with. Other reasons could be that a product is not yet part of an existing certification scheme or that brands are no longer willing to pay licensing fees.

Going beyond certification may imply that these companies work with shortened supply chains and aim for high transparency and traceability from source to consumer. This does not mean that certification is no longer required: it is and most likely will remain a much-used tool to guarantee fair trading principles.

In Europe there are numerous ethical trading companies that only source certified products while also aiming to go beyond certification. These include GEPA (Germany), Fairtrade Original (the Netherlands) and Ethiquable (France). Each of these companies is specialised in the import, sale and marketing of fair trade products.

Research shows that, in many cases, strong relationships between suppliers and buyers and ethical buying practices of buyers influence supplier performance instead of social audits. Ethical trading companies tend to invest in strong buyer-supplier partnerships, while adhering to ethical buying practices. In addition, these companies are keen to know the origin and story behind the products they source as they use this information to build their brand and market share.

Tips:

- Be willing and open to invest in transparent and long-term business relationships if you want to do business with these type of ethical trading companies. This implies that you must comply with buyer requirements and keep your promises. Doing so will provide you with a competitive advantage, more knowledge and stability on the European market.

- Know the ins and outs of your product and practices and be willing to openly share this information with buyers. You may also decide to provide your buyers with stories, pictures or videos to show their social aspects.

- Contact potential buyers in your target segment, or visit their websites to find out which standards or certifications are preferred. Buyers may have preferences for a certain sustainability label depending on their end clients and/or distribution channels.

Certification standards adapt to rising sustainability concerns

With sustainability becoming more and more important in Europe, the discussion of what socially responsible business practices entail may evolve. For example, the discussion around living wages and a living income has gained increased attention in recent years. A growing number of companies in Europe will take this into account when looking for new suppliers.

Certification standards and social compliance systems aim to adapt to these changing concerns. Fairtrade International and Rainforest Alliance, for instance, are active members of the living wage coalition. Fairtrade has worked with established minimum prices and premiums paid to farmers, but launched its Living Income Reference Price in 2020. At the same time, Rainforest Alliance also addresses living wage in its new certification programme. The Ethical Trade Initiative and SA8000 create awareness for living wages, by including the topic in their sets of requirements.

Tips:

- Take a look at the website of the Global Living Wage Coalition to learn about the concept of living wage, and how it is calculated. You can also find more insights into specific region’s living wage.

- Make sure you pay a living wage to your producers and/or workers. Have a look at WageIndicator website for an indication of living wages in your country. Keep records related to your employees’ pay and work hours for accountability.

- Keep up-to-date with the requirements of the certification schemes and standards you work with, as they are subject to change. For fish, for instance, regularly check the website of ASC. It contains lots of information about the standard and publishes a monthly ASC certification update.

Caution: supply of certified products may overshadow demand in some sectors

Although demand for certified products is increasing, in several sectors there is still a mismatch between supply and demand of certified products. In some sectors, certification standards are seen as a factor contributing to overproduction. Specifically for cocoa, it is said that the attractive price premiums of some standards have led to overproduction. Based on interviews with traders, some sources indicate that this has resulted in declining prices in West Africa in the last decade.

Figure 5 shows the misbalance between supply and demand for certified products. A little less than 30% of total Fairtrade-certified produced cocoa was actually sold as certified in 2020. For bananas, 54% of Fairtrade-certified produced bananas were sold as such, and for Fairtrade produced coffee that number was just 25%. For Rainforest Alliance, shares of certified product sales of total production volumes were: 29% for bananas, 57% for cocoa and 52% for coffee. In the case of UTZ, 68% of UTZ produced cocoa was sold as such, and 57% of UTZ-certified coffee. That means that many producers are not able to sell (all) their certified products at a premium price as they have to sell their products on conventional markets, while they did make the investments to certify farming operations. This may put farmers at financial risk.

Due to the imbalance between production and sales of certified products, some standards have taken additional measures to counter this. As of mid-2020, Fairtrade has introduced new requirements for certification for coffee and cocoa. Coffee and cocoa cooperatives and traders are now required to have commitments for new Fairtrade sales volumes, which must be confirmed by the end buyer and validated by the respective national Fairtrade organisation.

* Although Rainforest Alliance and UTZ merged in 2018, full mutual recognition for cocoa and coffee comes into force as of 2022, when all volumes will be changed to Rainforest Alliance volumes regardless of the original programme.

**Data has not been corrected for double certification.

Tips:

- Before engaging in any certification schemes, verify with your potential buyers whether a certification is required or demanded on your target market and whether it provides you with a competitive advantage over other suppliers. You could also discuss with your buyer if there are any possibilities of receiving assistance in obtaining your certifications. You can also prepare for certification but hold off on the actual audit until you have confirmed interest from a potential buyer.

- Besides promoting your certification, also promote other sustainable and ethical aspects of your production process. Transparency and traceability in the supply chain have become increasingly important, having well-documented information on your products can give you a competitive advantage. You should be able to prove and communicate a clear and direct link between producer and consumer.

- If you decide not to certify your product, find other ways of showing your buyer that your product is produced sustainably. Verify the sustainability of your product by comparing it to your buyer’s sustainability codes or questionnaires, for example. Buyers want proof, so document your findings and explain how you will solve key sustainability risks and issues. You can for instance refer to the self-assessment templates of amfori or the self-assessments questionnaires of the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) Platform to document your findings.

Drive for standardisation in certification schemes and standards

This study includes several examples of social certification standards, out of 400+ voluntary standards available to companies. Where the early 2000s marked a time where multiple new standards were created, currently there is a growing call for standardisation of such standards.

For consumers, the wealth of labels is starting to cause label fatigue: there are too many labels on products for them to know what they all mean. This is a threat to certification standards, which risk being drowned out by competing certifications.

On the side of suppliers, it is difficult to comply with lots of different audits that require substantial investments in money, time, and other resources. For example, fresh fruit importers supply products to European buyers who need SMETA, buyers who need BSCI and/or buyers who expect compliance with GRASP standards. As such, importers generally require their own exporting suppliers to participate in all these schemes. Excluding costs of implementing these standards, certification costs may amount to €1,000–€1,500 per certificate. Although large producers can afford to do so, small companies struggle to make these investments.

Some certification standards respond to these developments by recognising other standards as equivalent, such as Fair for Life which allows for possible recognition of ingredients certified according to Fairtrade, FairWild, SPP, Fair Trade Certified (FT USA) and Naturland Fair. The 2018 merger of Rainforest Alliance and UTZ goes even further. In addition to providing certified producers access to additional markets and growing consumer interest, the certifiers also expect this will help brands to simplify their message and prevent a proliferation of messages that can confuse consumers. At the same time, this merger can also be a response to the demand for greater efficiency and effectiveness.

There is also a growing number of initiatives which are benchmarking different schemes and standards. These initiatives aim for traders and retailers to accept different schemes that have been benchmarked positively, instead of only requiring one specific scheme. This will reduce the pressure on suppliers to comply with a wide series of different standards. Examples of these initiatives include the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative (GSSI) for fish and seafood and the Higg Index for apparel. In addition, you have the Global Social Compliance Programme (GSCP), which also aims to create a common understanding of best practices for sustainable supply chain management.

Tips:

- When making your decision to select a social certification standard, find out which standards are most commonly required or used in your sector. If your buyers demand multiple certification schemes, determine if there is any overlap between the different standards and certification bodies and see if you can combine audits or create other synergies.

- Refer to ITC’s State of Sustainable Markets 2021 and the Sustainability Market Trends Dashboards for more information on trends, figures and developments in certification schemes.

- Investigate which social certification schemes are in line with the Global Social Compliance Programme. These schemes generally have a higher chance of being accepted by European retailers.

4. What are the most demanded social certification standards in Europe?

Which certification standard is most demanded differs largely per sector. In general, Fairtrade, Fair for Life and Rainforest Alliance are among the most demanded product certification standards in the agro-food sectors. In the non-food sectors, buyers often require suppliers to comply with social compliance standards. BSCI, ETI and Sedex are among the most requested by European buyers.

Most demanded product certifications in agro-food sectors

Based on a series of interviews and the specific market studies available on our CBI Market Information website, the following table lists the most common social certification standards for products, specified per sector.

Table 2: Most common product certifications with social criteria requested by European buyers in agro-food sectors

| Cacao | Coffee | Fresh Fruit & Vegetables | Processed Fruit & Vegetables & Edible Nuts | Grains, Pulses and Oilseeds | Spices and Herbs | Natural Ingredients for Cosmetics | Natural Ingredients for Health Products | Natural Food Additives | Fish and Seafood | |

| Rainforest Alliance |

| |||||||||

| Fairtrade | ||||||||||

| Fair for Life | ||||||||||

| FairWild | ||||||||||

| Small Producers Symbol (SPP) | ||||||||||

| Common Code for the Coffee Community (4C) | ||||||||||

| Union for Ethical BioTrade (UEBT) |

| |||||||||

| Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) | ||||||||||

| Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) |

* In 2022, the Rainforest Alliance and the Union for Ethical BioTrade (UEBT) developed a joint Herbs & Spices Program. All ingredients certified under this new program will be able to carry the Rainforest Alliance Certified seal.

As the above table shows, the most common product certification standards across all sectors are:

- Fairtrade: Fairtrade International (FLO) has set standards to improve the living conditions of southern producers. More than 1.9 million farmers and workers from 70 countries are involved in Fairtrade. The Fairtrade mark is the most recognised ethical label globally, with certified products being sold in 131 countries.

- Rainforest Alliance/UTZ: Rainforest Alliance aims to preserve biodiversity and improve working conditions. There are more than 2.3 million Rainforest Alliance and UTZ certified farmers, mainly from the coffee, cacao and tea sectors. Consumers in 100 countries can buy products with the Rainforest Alliance or UTZ label.

As of early 2022, there is full mutual recognition for cocoa, hazelnuts, tea, coffee, herbs and spices, processed fruits (including coconut oil) and flowers. This means that volumes of these products that are certified under the old Rainforest Alliance standard, UTZ and/or the new Rainforest Alliance programme are all considered ‘Rainforest Alliance’ (i.e. regardless of the original programme).

- Fair for Life: There are about 100 companies certified and 100 operations registered according to the Fair for Life (FFL) certification programme. Producers and brand holders must be certified, while traders and processors suffice with registration. Over 3,000 Fair for Life products are sold at mainstream and specialised retailers, with sales concentrated in about 20 countries.

Global production and sales size of Rainforest Alliance/UTZ and Fairtrade

Rainforest Alliance/UTZ and Fairtrade certification have shown significant growth both in terms of production and sales across most sectors over the last ten years. The below figures provide an overview of the production and sales volumes development between 2016 and 2020 of three main commodity products: bananas, cocoa and coffee. The figures show how certified volumes showed an upward trends. In the case of cocoa there is a noticable decline, mostly due to a ban on dual certification per 2020 for Ghana and Ivory Coast as well as strong requirements on GPS data for cocoa. Demand for certified cocoa, however, is expected to take the same course as the other products in that it is likely to increase or remain stable. Still, supply is expected to remain much larger than market uptake of certified products.

Largest Fairtrade markets in Europe

Germany is the largest Fairtrade market in Europe, with retail sales of Fairtrade-certified products amounting to almost €1.45 billion in 2020. Between 2019 and 2020, sales registered an annual decline of -3.2%. After more than a decade of growth, Fairtrade sales in Germany declined for the first time as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The main Fairtrade-certified products sold in Germany were coffee, cocoa, textile, bananas and flowers.

The United Kingdom is another large Fairtrade market with annual Fairtrade retail sales reaching about €1.2 billion in April 2021, registering a value sales growth of almost 14% compared to the year before. It illustrates that people are becoming even more open to ethical consumption in the UK. The size of the UK market is in part thanks to partnerships between retailers and Fairtrade. For instance, retailer Sainsbury’s offers almost 27% of total Fairtrade-products on sale in the UK. Sainsbury’s is the UK’s second-largest supermarket chain.

France is the third-largest Fairtrade market in Europe. In 2020, Fairtrade retail sales in France reached €1.0 billion, marking a growth of 12% since 2019. Another important Fairtrade market is Switzerland, with annual Fairtrade retail sales of nearly €831 million in 2020. Between 2019 and 2020, retail sales of Fairtrade products in Switzerland increased by 5.6%. Swedish Fairtrade market amounted to €467 million in 2020, also registering growth of 11% despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

Annual Fairtrade per capita consumption is highest in Switzerland with almost €96. To compare, the per capita consumption of Fairtrade products in Germany amounted to €24 and in Austria €46.

Rainforest Alliance market in Europe

The merger between UTZ and Rainforest Alliance in 2018 has resulted in a large market for Rainforest Alliance products across Europe. As full mutual recognition for certified products will only enter into force as of early 2022, data on UTZ and Rainforest Alliance markets are still given separately.

One way to look at the size of the market in Europe is to see how many UTZ-certified supply chain actors are active on a particular market. This indicates the largest markets are Germany with 320 actors active in December 2021, followed by the Netherlands with 253 and Italy with 213. Other important markets are Belgium (133), the UK (116), Switzerland (110) and Spain (103). Cocoa is the largest UTZ-sector in terms of certified supply chain actors.

Germany also hosts the most Rainforest Alliance-certified supply chain actors (140 in December 2021). The United Kingdom (98) and the Netherlands (76) follow as the second and third-largest. These three markets offer the largest assortment of Rainforest Alliance-certified products. For instance, German retailers Edeka, Rewe, Kaufland, Penny and Lidl have private label products certified by Rainforest Alliance. Italy, Switzerland and Spain follow with a number of actors ranging between 40 and 50.

Logo recognition is another way to look at the importance of Rainforest Alliance in several European markets. By looking at logo recognition, slightly different markets come forward as most important. According to data from 2019, 62% of consumers from the UK recognise the Rainforest Alliance logo, followed by 48% of Swedish consumers, 38% of German consumers and 34% of consumers from the Netherlands.

Fair for Life market in Europe

There is little data available on the size of the Fair for Life market. By far the largest market is France with well over 170 registered and certified companies in 2021. Germany follows as the second-largest market with 35 companies dealing with FFL products, followed bly the Netherlands with 22, Switzerland with 14 and the United Kingdom with 11 companies registered and/or certified by Fair for Life.

The Fair for Life certification programme was launched in Switzerland in 2006. In 2017, Fair for Life and the global French-based organic certification organisation Ecocert merged into Fair for Life certification as we know it today. It partly explains the large presence and popularity of the label in France.

Social certification for natural ingredients

Social standards are important in all food sectors, and increasingly so due to new legislative requirements on European level. Still, some sectors put a larger emphasis on certification than others. Product certification with social standards such as Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance are most used in commodity food value chains, such as coffee, cocoa, tea, fruits and sugar.

For natural ingredient sectors (including herbs, oils, extracts, among others) the use of and demand for certification is less clear-cut. Whether or not European buyers are interested in buying certified natural ingredients depends on how buyers communicate this to their customers. For instance, industry sources indicated that 80-90% of spices and herbs are used as food ingredients, instead of final products. When a spice makes up a small share of a product, it is difficult to communicate its sustainability to consumers. European food manufacturers may be more interested in certified spices and herbs if they are part of an entirely certified food product.

In the case of natural ingredients for cosmetics, manufacturers more often choose certified ingredients as a means to support their brand image as ethical. This means they often adhere to fair trade principles, though their final cosmetic products are not necessarily certified as such. This has several reasons. For one, because cosmetic products commonly contain at least 10-20 ingredients. Moreover, most cosmetic products consist for up to 90% of water, which cannot be certified as fair trade.

Not all social certification standards cover cosmetic ingredients. Fairtrade, for instance, is limited to ingredients mainly used in food, such as cocoa and shea butter, coconut oil and sugar. For final cosmetic products to be able to have a Fairtrade label on their packaging, they need to contain at least 5% of Fairtrade ingredients in leave-on products and 2% in rinse-off products. However, this does not mean that cosmetic companies do not work with Fairtrade. The German cosmetics company Fair Squared is an example of a company using Fairtrade certified ingredients in its products where these are available.

Standards such as Fair for Life and FairWild can be adapted to a much larger variety of products and ingredients. Both have separate criteria for sustainable wild harvesting of plants, while Fair for Life can also be used for cultivated ingredients. These standards are more commonly used for natural ingredients, though some cosmetic brands choose to focus on Fairtrade certification, likely using the existing consumer awareness of this certification from their use in food sectors.

Tips:

- Check the websites of the national Fairtrade organisations in Europe to stay up-to-date on developments in a specific market. National Fairtrade organisations license the Fairtrade marks on products and promote Fairtrade in the country.

- Be aware that different countries/regions value different aspects of sustainability. For instance, Fairtrade products find a very large market in the UK, while Germany is the largest market for organic-certified products. In general, in North and Western Europe sustainability has become a leading theme in purchasing decisions for many consumers. In recent years, however, demand for sustainable products is also on the rise in Southern and Eastern Europe. In general, these markets still lag slightly behind in terms of demand for sustainability/certified products.

- Check the annual reports of certification standards to search for latest data on retail sales and more. These can be find on their websites. Also, do not forget to consult the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). Be aware that information can be hard to find, and sometimes only available in a language other than English.

- Find potential certified business partners in Europe by checking the lists of Fairtrade-certified operators, Rainforest Alliance/UTZ-certified supply chain actors, Fair for Life-certified operators and Fair Wild-certified operators.

- Understand why buyers decide to work with specific certification schemes. For instance, refer to this story by the tea brand Pukka (UK) and understand why they are Fair for Life certified.

Most demanded standards in non-food sectors

There are several certification schemes that were specifically developed to certify non-food products. Based on interviews and our studies about sustainability in home decoration and home textiles (HDHT), sustainable materials and sustainable apparel, the table below gives an overview of the most commonly demanded certification standards that include social critieria in these European non-food sectors.

Table 3: Most common product certifications requested by European buyers in non-food sectors*

| Apparel | Materials | HDHT |

| Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) | Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) | World Fair Trade Organisation (WFTO) |

| OEKO-TEX (Made in Green) | Cotton Made in Africa (CmiA) | Fair for Life |

| Fairtrade | Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) | |

| Organic Content Standard (OCS) | OEKO-TEX (STEP) | |

| Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) | Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) |

* Some of these standards include, besides social criteria, very strong environmental elements (examples: GOTS and OCS).

In general, most European buyers in the HDHT and apparel sectors do not demand certification. Instead, many buyers increasingly demand their suppliers to comply with certain social compliance standards. With these standards buyers want to ensure that the products they source are produced in fair and safe working conditions. The most common requested standards in Europe are:

- amfori Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI): This is a suply chain management system that helps manufacturers drive social compliance. The amfori BSCI Code of Conduct includes 11 principles, ranging from fair remuneration to no child labour. To prove compliance, a European buyer can request a third-party audit of a supplier’s production process. If you get audited, you will be included in a database together with all BSCI members.

- Ethical Trade Initiative (ETI): This initiative is an alliance of companies, trade unions and voluntary organisations. It aims to improve the working lives of people across the globe who make or grow consumer goods. The ETI Base Code consists of 9 principles, one of them being the payment of living wage. It is possible to audit your company for ETI compliance.

- SMETA: Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit: This guideline does not specify a particular code, instead it stores information on ethical and responsible practices covered by ILO Conventions, ETI Base Code, SA8000, ISO14001 and industry specific codes of conduct. Sedex members can use the information on the system to evaluate suppliers against any of these codes or the labour standards provisions in individual corporate codes.

The above standards are applicable to companies of all sizes and from all sectors. Even if these standards are not requested by your buyer, you can still use their guidelines to assess your sustainability. For instance, complete the Self-Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ) to identify important ethical, social and environmental issues in your business and share this with (potential) buyers. Altough non of the above-mentioned standards provide certification, they show European buyers that you are actively working on and are concerned with social sustianability within your company.

In which markets are most member countries of these initiatives found?

ETI is most requested by buyers from the UK. Among the members of ETI are also UK’s three largest retailers: Tesco, Sainsbury’s and ASDA. With over 500 member buying companies, the UK also has by far the largest number of Sedex buyers, followed at a large distance by the Netherlands (34), Germany (30), Ireland (16), Spain (16), Italy (14) and France (12). BSCI finds its largest company member base in Germany (850 members), followed by the Netherlands (411), France (191) and Denmark (162). This is just an indication of what you may expect from specific countries. In the end it depends on your buyer’s preference which standard is required, if any.

Tips:

- Create your company’s code of conduct based on the codes of amfori BSCI Code of Conduct, the ETI Base Code or Sedex’s SAQ.

- Discuss sustainability concerns and specific social requirements with your (potential) buyers. You can use these insights to comply with buyer requirements, as well as to build a story for marketing purposes about these specific sustainability aspects.

- Refer to the specific factsheets on sustainability in HDHT, the sustainable transition in apparel and home textiles, and buyer requirements for apparel and materials for more insights into sustainability issues and requirements in these sectors.

5. What are the main differences between the most demanded social certification standards?

The standards for Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance and Fair for Life vary across several indicators. Of these standards, Fair for Life covers the widest product range and allows for recognition of ingredients certified according to other standards, which both Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade do not. Regarding eligibility, Fairtrade is most restrictive, both in terms of geography and type of actors that can be certified. Fairtrade is also the only standard of the three that works with a guaranteed premium. Rainforest Alliance and Fair for Life include more extensive environmental sustainability criteria than Fairtrade, which is often used in combination with organic certification.

Table 4: Main differences between Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance and Fair for Life standards

| Fairtrade | Rainforest Alliance | Fair for Life | |

| Products | Cereals, cocoa, coffee, seed cotton, flowers and plants, herbs, spices, processed and fresh fruit and vegetables, sports balls, sugar, honey, nuts, oil seeds. | Cocoa, tea, coffee, rooibos, palm oil, hazelnuts, bananas, seeds, flowers and foliage, vegetables and spices. | All natural products from agriculture, wild collection, aquaculture, livestock, and beekeeping, as well as handicrafts. |

| Standards / Equivalance | Standards for small-scale producers, hired labour organisations, for contract production and for traders. Specific Fairtrade standards for each product. Fairtrade International does not recognise any other label as equivalent. | There is a 2020 Sustainable Agriculture Standard specific with Farm Requirements and one with Supply Chain Requirements. The standard differentiates between smallholders and large producers. Rainforest Alliance does not recognise any other label as equivalent. | One standard that covers all products. Eligble products include more specialist fair trade products such as herbal teas and essential oils in addition to cocoa and fruits. Possible recognition of ingredients certified according to: Fairtrade, FairWild, SPP, Fair Trade Certified (FT USA), Naturland Fair. |

| Who is eligible? | Geographical scope: There is a restricted geographical scope with ‘developing’ countries and territories where producers are eligible for Fairtrade certification. Type of actors: Certified producers’ organisations, hired labour. | Geographical scope: Both ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries. Type of actors: All farm sizes, including large estates, and companies. | Geographical scope: Both ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries. That means that buyers in countries like Turkey are also eligble. Type of actors: Farmers, growers, hired labour, packers, employees, traders, processors, etc. |

| Costs | Costs depend on various elements. To give a price indication, the certification body FLOCERT provides a cost calculator that will produce an estimate of certification cost. | Costs vary depending on work, needs, size of the farm and location. Costs for farmers include: - costs associated with meeting the Sustainable Agriculture Standard. As smallholder farmers you can organise yourself and seek certification as a group to reduce expenses. An overview and examples of costs for companies can be found here. | Certification costs vary depending on the location and size and complexity of your operation/ supply chain: a quote is given at the start of the process. You can send an applicatin form, after which an offer will be prepared. You will then be asked to confirm your application and approve the estimated costs by signing the offer and the certification contract. If you are already certified organic by Ecocert or IMO, this reduces the cost of Fair for Life certification, as the audits can normally be combined. |

| Prices/income | Guarantees Fairtrade Minimum Price, social premium and, if applicable, organic premium. When the market price for a product is higher than the minimum price, the market price has to be paid. No Fairtrade minimum prices are defined for secondary products and their derivatives. These prices have to be negotiated between producer and buyer. Premiums need to be paid for each product, including secondary products. Premium is paid to farmer organisation, not to individual farmers. | No guaranteed miminum price. However, RFA works with a Sustainability Differential and Sustainability Investment requirement. Sustainability Differential: mandatory additional cash payment, decided through negotations between buyer and seller. There is no restriction on how the differential should be used. Sustainability investment requirement: buyers must make cash or in-kind investments to farmers based on the needs identified in farmers’ investment plans. | Prices are negotiated and agreed between sellers and buyers; a floor price should be determined based on sustainable production costs calculations. Sales prices are aimed to be at least 5-10% above conventional market prices, but this entirely depends on negotiation outcomes. On top of the sales price, a premium must be paid into a separate fund for community projects at the producer level. |

| Inclusion of environmental sustainability | Includes criteria about responsible water and waste management, preserving biodiversity and soil fertility, and minimal use of pesticides and agrochemicals. Fairtrade prohibits the use of several hazardous materials and all genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The combination of both Fairtrade and Organic-certified products is increasingly common and continues to gain populairty in Europe for sectors like coffee. | Extensive coverage of environmental criteria is included in the standard. Environmental criteria promote healthier soil, cleaner water, reduced use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, biodiversity conservation, and climate change adaptation and mitigation. | Standard includes aseries of criteria related to environmental sustainability, biodiveristy, ban on GMOs and prohibition of hazardous substances. Organic certification is not necesary but highly encouraged by Fair for Life. |

The social compliance standards BSCI, ETI and SMETA are all based on international labour standards. Of these standards, SMETA includes the highest share of environmental criteria (if you chose the 4-piller audit). Regarding eligibility, companies from all sizes and sectors can be required by their buyers to get an audit. Benefits for each standard are fairly similar, and all aim to avoid unnecessary duplication efforts for suppliers in their own way. Still, buyers often have the final decision on which standards they request and to what extent they recognise standards as equivalent.

Table 5: Main differences between BSCI, ETI and SMETA standards

| BSCI | ETI | SMETA | |

Which principles are included in the standard?

/

Equivalence | The amfori BSCI Code of Conduct draws on international labour standards protecting workers’ rights such as International Labour Organisation conventions and declarations, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights as well as guidelines for multinational enterprises of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The Code of conduct is organised around 11 social principles:

BSCI recognises SA8000 for 100% and Rainforest Alliance as 80% equivalent. | The ETI Base Code builds on the standards of the International Labour Organisation, and consists of 9 principles:

Companies applying this Base Code should also comply with national and any other applicable laws.

ETI is viewed as a global reference standard and is widely used as a benchmark against which to conduct social audits and develop ethical trade action plans. | You can choose between a 2-Pillar and 4-Pillar SMETA audit.

SMETA 2-Pillar audits are governed by the standards contained in the ETI base code, focusing on labour standards and health and safety.

To these criteria, SMETA 4-Pillar audits add additional environmental management requirements as well as ethical business practices.

All social audits (examples: BSCI, WRAP, SA 8000) can be uploaded onto Sedex platform. It is up to your buyer to decide which audit is accepted by them and best suits their purposes. |

| Who uses this standard? | The amfori BSCI is aimed at companies operating on the international market and cooperating with supplier companies abroad. The supplier audits fit best with companies looking to strengthen their responsible corporate action, both internally and in the supply chain. For a supplier, this means you can be requested to undergo an audit. This audit will be applied for via the amfori BSCI platform and approved by the amfori BSCI member (your buyer). | The Base Code of ETI is a generic code of labour practice. For ETI member companies and many other retailers and brands it is interesting to adopt this code. Some companies adopt the code literally, others incorporate it into their own company’s code of conduct. Either way, ETI member companies and many others increasingly make sure that their suppliers work towards compliance with the code over time and inspect large numbers of their suppliers against the Base Code every year. | Buyers often use SMETA audits and the Sedex database to productively manage and mitigate risks in their supply chains, by following the principles of SMETA. Members of SMETA, however, include suppliers, importers and exporters. Buyers can request their suppliers to undergo an audit. As a supplier you can publish your Sedex reports to the database. |

| How is auditing done? | As explained by Tüv Rheinland, before an audit each producer is asked to fill out the BSCI self-assessment questionnaire. This gives auditors a first impression and supports the audit planning. The supplier then receives an audit plan with a list of documents needed for the audit. When an audit is carried out on site, auditors examine whether the supplier adheres to the guidelines of the amfori BSCI Code of Conduct.

Social audits are done by external accredited entities, that check social activities of companies along the supply chain. | Audits are done by auditing companies with experience of carrying out audits against the ETI Base Code.

Note that audits are meant to be a way of diagnosing problems, not as a ‘pass or fail’ test. As ETI states: “It is rare to find any company that is fully compliant with the Base Code. If you supply an ETI member company, you should expect them to help you make any necessary improvements within a timeframe that works for both of you. ETI member companies should not stop trading with you if the audit uncovers only minor issues. However, if they uncover very serious issues, you will be expected to take immediate corrective action. If you do not do so, you may lose the business.” | If decided to go for a third-party audit, this is done by affiliate audit companies.

After a successful SMETA audit, you can register with the Sedex platform, where registered companies openly share information about their social and ethical performance with other members and customers. The Sedex database is a globally recognised online platform.

|

| What are the benefits? | Some of the listed benefits include:

| Some of the listed benefits include:

| Some of the listed benefits include:

|

Tips:

- Refer to the International guide to fair trade labels. This is a reference document to better understand the guarantees of fair trade labels, their standards, monitoring measures and how they differ from sustainable development labels.

- Check out the training possibilities of certification schemes. For instance, Rainforest Alliance offers both online and in-person trainings for best practices in sustainable agriculture, such as this training on the 2020 Sustainable Agriculture Standard.

- Refer to this document for a comparison of the ETI Base Code and SA8000.

6. What are possible benefits of social certification standards?

For SMEs there are different reasons to obtain certification. Examples include demand by your buyer, ensuring transparency and traceability, improving company reputation, dealing with specific social issues in your chain, and/or adding credibility to your sustainability claims.

Social certification standards claim various benefits by obtaining their certification. These generally include that certification contributes to achieving Sustainable Development goals, that you receive a fair price for your products and thus improve the livelihoods of smallholder farmers and that companies can demonstrate that they are reliable partners that are serious about (social) sustainability. Research has shown that the benefits and impact of social certification may vary per standard, region or company/cooperative that obtains the certification. Moreover, as supply of fair trade products exceeds demand, not all certified products can be sold as such.

Table 6: An overview of different possible benefits of social certification standards

| Possible benefit | Explanation / impact |

| Higher / fair price for your products | Most social certification standards include fair prices for products. For example, Fairtrade states: “We put fair prices first because farmers and workers in developing countries deserve a decent income and decent work”. Research conducted on the impact of social certification standards often indicate a positive effect on prices for certified products. In the case of Fairtrade, this comes from the minimum price for products, while studies on Rainforest Alliance/UTZ certification attribute small price increases to improved product quality. When you take certification costs and administration time/costs into account as well, price increases are relatively small. |

| Higher household income | Although results vary among studies, positive impacts have been found on household income for producers of certified products. Fairtrade International claims that a review of 151 studies found Fairtrade “improves farmers’ income, wellbeing and resilience”. Fair for Life adds that with certification “your company and its fair trade contribution can effectively improve the livelihood of many smallholder farmers and/or workers”. Other positive impacts have been on assets, food security or education. Studies looking at net household incomes for certified coffee, excluding certification costs, find limited evidence of overall improvement. Results vary depending on the effectiveness that cooperatives have in representing, managing and communicating with producers. |

Working conditions

| Obtaining certification demonstrates that your company and its products meet social criteria in a recognised standard. A review of studies on outcomes of Fairtrade certification finds that certification:

Fair for Life adds that workers “enjoy excellent working conditions” while Rainforest Alliance states that “Rainforest Alliance Certified farms are better and safer places to live and work”. Moreover, auditing your performance on social criteria can bring social performance to the attention of management and provides a formal procedure to assess and improve social performance. These criteria can help to assess workplace health and safety conditions, review documentation and develop reporting. Studies on various social certification standards in the coffee sector find some positive results on working conditions, but results are mixed. Some find improvements in working conditions, but these improvements are not sustained and often the findings are that certification has little or no effect on labour standards compliance or working conditions. |

Credibility and company reputation

| As third-party certification is verified by an independent control body, it demonstrates your company’s commitment to social sustainability by complying with a specific standard. This helps to show your credibility and strengthen your reputation towards potential buyers. You can use it to build trust within global supply chains. Fair for Life adds: “Consumers can buy your products in confidence with the assurance that the products are produced in a truly sustainable and accountable way”. |

Market access

| Obtaining social standard certification can help you to access new markets or stand out in existing markets. You can use it to distinguish your company as a socially responsible operation and communicate the integrity of your company and its products. Which standard has most added value for you depends on your product, end-market and type of buyer you target. For some products, such as cocoa and coffee, it may be very difficult to enter international markets without certification. Fairtrade International finds that the label “raises consumers’ awareness, commitment and willingness to pay for fair and sustainable consumption”. Studies support the link to end markets, adding that having a strong relationship with buyers is associated with more positive outcomes of the certification. |

Risk reduction

| Increasingly, financiers build portfolios that avoid social and environmental risks. In sustainable finance, they integrate environmental, social and governance criteria into business or investment decisions. Some financiers use voluntary standards as a comprehensive and credible tool to monitor risks in business operations. This also recognises that certified companies lower their sustainability related risks. For example, in Ghana, sustainable businesses can get loans with lower interest rates, as banks consider them less risky. |

Traceability

| To achieve a social certification, companies must have a satisfactory traceability system in place. Certified products need to be kept separate from non-certified products and companies need to track and audit volumes sold through the supply chain. An added benefit is that certified companies have a better knowledge of their farm or raw input source. With the continuously growing demand for traceable products in international markets, this can be an added value to obtain certification. |

Quality and Productivity

| Having a social certification can, indirectly, also help you to increase product quality and productivity. This is often due to training that is offered, or improved processing facilities, not a direct result of certification itself. Some exceptions include FairWild certified products, which emphasises on good collection practices and resource assessments that may support increased quality and productivity. Rainforest Alliance adds that “Certified farmers and foresters are able to grow better crops, adapt to climate change, and increase their productivity”. This has been supported by some studies, but productivity effects are not commonly reported on. Looking at the coffee sector, studies on Fairtrade certification show lower impact on productivity as the standard emphasises trading relationships and prices over agricultural practices. |

Environmental impacts

| Some of the social certification standards mentioned in this study claim environmental impacts, most notably FairWild and Rainforest Alliance. FairWild states that if a supplier obtains FairWild certification, “buyers, whether ingredient traders or consumers, know they are dealing with legally and sustainably harvested products”. This standard focuses strongly on sustainable management and collection of wild resources, to ensure future availability of resources. Rainforest Alliance explains that “certified farms are also better for the planet and more sustainable in the long term. This is because certified farmers must protect natural resources and the environment.” However, for other social certification standards this outcome is less clear as the focus is on social responsibility. There are some indications that having obtained a social certification standard may make it easier to obtain organic certification which has a stronger environmental impact. |

Tips:

- Make a thorough cost calculation to calculate the possible extra profit if you decide to pursue certification. Do the calculation with and without the certification fees, learning costs, workload and possible differences in yields. Realise that the price you may obtain for your certified products may range widely, depending on the quality of your products and certification scheme.

- Make sustainability part of your core business. Try to provide a fully traceable product, improve your control over the supply chain, make your production more sustainable, invest in farmers and train them on sustainability issues.

7. What are hurdles related to social certification standards?

Though certification of social standards can lead to several possible benefits as highlighted in chapter 6, they are not without their challenges. Before determining whether certification is the right move for your company, and which standard offers the most opportunities, you need to have a good understanding of the hurdles you can expect.

Table 7: An overview of different possible hurdles related to social certification standards

| Possible hurdles | Explanation / impact |

| Total certified market is limited | One of the key challenges for certification is that, for some products, supply is much larger than demand (see trends section for more information). The market for certified products, though growing, is small and several producers of commodity products cannot sell their volumes produced in the certified market. You will need to invest time and resources to obtain certification but may not have a guarantee that you will find buyers that value that effort. If you need to sell certified products in conventional trading channels you may not have sufficient income to cover the costs of certification. |

| Limited consumer recognisability | Most suppliers in the business-to-business (B2B) trade rely on final product manufacturers or retailers to promote social certification labels to expand future demand. However, lesser-known standards, such as FairWild, or those that are not commonly used on final products, such as Fair for Life in the cosmetic industry, are generally less visible to end-consumers. At the same time, some buyers may choose not to display labels of their certified products when selling to final consumers. Indirectly, this could diminish the future demand for certified products and thus the value of obtaining such a certification. |

| Limited applicability to small-scale producers | A common criticism of social certification standards is that they are not readily applicable for small-scale producers. Certification may not be commercially viable for small, low-productivity producers where the premium earned is too low to cover costs of certification. For example, some small-scale producers do not have the capacity to implement ASC or MSC standards at the fishery or farm level and it is too difficult to organise farmers to ensure chain of custody. Reviews of certified coffee producers demonstrated that certification tilted towards larger farms and groups that can tap into economies of scale or that already meet required criteria. These organisations can ensure quality that is sufficient, they have access to land, labour, education, and other resources, as well as access to markets that better value their products to make certification worthwhile. In cases where smaller, less educated or poorer farmers obtained certification, they were often supported by NGOs. One of the reasons the Sustainable Agriculture Network listed to no longer participate in certification schemes was that there were limits to the potential benefits from certification due to complexity, a low benefit-cost ratio, scaling issues and limited effectiveness. |