How to calculate the cost price of an apparel item?

You can only build a successful business relationship with a European buyer if you can calculate the cost price of your apparel items. Understanding every cost involved allows you to manage production efficiently and negotiate good deals with buyers. This document guides you through selecting the most suitable calculation method for your business and correctly calculating costs yourself.

Contents of this page

- Why is good cost-price calculation so important?

- What is retail mark-up?

- What are the differences in calculating cost price for common Incoterms?

- How to calculate your cost price

- Calculation sheet

- How important is production efficiency?

- How to determine the right price for your target market?

- How to reduce your cost price?

- How to be competitive

- What kind of payment terms are acceptable?

Disclaimer

This study and the accompanying calculation sheet in the annex use examples to explain how to calculate costs. Be aware that costs in your factory will differ from the examples in this study. Some cost items that occur in your factory may not be present in this study or the accompanying sheet. Always use accurate company data when calculating costs for real production orders. CBI is not responsible or liable for any outcomes that are the result of using this study or the accompanying calculation sheet.

1. Why is good cost-price calculation so important?

The factory price of your product includes many different cost items: labour, fabrics, accessories, employees, machinery, energy and more. Each of these costs can change, sometimes quickly. This may be due to different factors, such as climate shocks causing poor harvests, rising inflation, changes in the exchange rate and geo-political tensions, such as the war between Russia and Ukraine and security issues in the Red Sea.

One additional factor that drives up production costs is compliance with new social and environmental requirements. The EU is introducing legal requirements that increase costs throughout the supply chain as part of the ‘European Green Deal’. This includes directives concerning:

- Traceability and impact reporting: This includes the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD).

- Ecodesign for Sustainable (textile) Products Regulation. This sets requirements for durability, reusability, energy and resource efficiency, recycled content, a Digital Product Passport and more; and

- An EU-wide EPR (extended producer responsibility) levy for apparel.

Due to the combination of factors mentioned above, fabric prices have risen sharply in recent years – both polyester and cotton– and so have shipping costs. Labour costs have risen too, particularly in Asian production countries. These costs are central to European buyers’ sourcing strategies. When costs change, sourcing strategies change too. This is why you need to monitor all your costs regularly.

Note that ‘regularly’ means weekly or even daily – not just once per season. There was a time in the apparel industry when you could lock in the cost price of an order for six months or more, but those days are gone. Failing to review your cost factors regularly may lead to unexpected price increases and potential losses on your order. Monitor your costs often and you will be well-prepared for negotiations with buyers. It also helps prevent difficult discussions during production.

Figure 1: Rising shipping costs have made many buyers looking for alternative sourcing destinations

Source: Photo by william william on Unsplash

2. What is retail mark-up?

Manufacturers are sometimes surprised by the large difference between the FOB price (‘Free on Board’, see below) they get for their products and the price they are sold for in Europe. An item that leaves the factory for less than $20 might sell to European customers for €100 or more. Does this mean manufacturers are treated unfairly? Not necessarily, and it is important to know why.

Why do retail companies mark up the FOB price?

Retailers need to account for import duties, transport, rent, marketing, overhead, stock keeping, markdowns, VAT (15–27% in EU-countries), environmental levies and more. For this reason, the retail price of an apparel item is four to eight times the FOB price on average. This is called ‘retail mark-up’. It follows that the FOB price is on average 12.5-25% of the product’s retail price. There are exceptions. In the budget market, some large European retail chains focus on profit through volume and market share and may simply double the FOB price.

Figure 2: European retailers mark up FOB prices to account for costs such as renting stores in expensive high-streets

Source: Photo by Jordan Pulmano on Unsplash

3. What are the differences in calculating cost price for common Incoterms?

Which cost items should be included in your cost calculations? This depends on the delivery terms you agree on with your buyer. It may vary from CM (cut-and-make) to CNF (cost-and-freight). The difference in cost items means a different way to calculate the cost price.

International commercial law has defined several terms to help buyers and suppliers communicate clearly about the tasks, costs and risks associated with international transportation and delivery of goods. These terms are called Incoterms (International Commercial Terms). The most-used Incoterms in the apparel industry are:

- CM (Cut & Make)

- CMP (Cut, Make & Packing)

- CMT (Cut, Make & Trims)

- FOB (Free on Board)

- CNF (Cost and Freight)

CM

This manufacturing method is only focused on the added value of labour. The factory does not supply any fabrics or trims, but it bears responsibility for the manufacturing process. The factory cuts the fabrics into pieces, stitches the pieces into one product and makes sure the items are properly packed. The buyer supplies all the fabrics, trims and packing materials. This way of manufacturing is very basic and it has low profits, but the risks involved are low too. Profits mainly depend on the speed of the production process, on time delivery and minimising the repair rate and mistakes.

CMP

CMP is similar to CM, but the factory is also responsible for arranging the packing materials. Because materials like cardboard boxes and polybags are often available locally, buyers prefer the factory to order these materials directly and include them in the costing.

CMT

CMT includes the trims, such as zippers, buttons, hang tags and labels. If these are available locally, then buyers often prefer the factory to order and manage the delivery of the trims. Organising the trims in countries that lack a local industry that produces trims is often complicated and likely quite expensive.

FOB

FOB is the most used Incoterm in the apparel industry. Most buyers prefer the factory to manage the production of the complete product. As a manufacturer, you are responsible for sourcing the materials, producing the apparel item, packing it and handing it over to the nominated forwarder.

Buyers may sometimes want you to buy fabrics, trims, packaging or other materials from a nominated supplier. In most such cases, buyers will have negotiated the price of the materials. This means it will not be possible to calculate any additional profits on the materials purchased from the nominated supplier.

CNF

In addition to the cost items mentioned under CM, CMP, CMT and FOB, CNF orders include the costs for shipment, insurance and transport to the buyer’s warehouse. This way of doing business is risky and costly for you as a manufacturer. Buyers may prefer manufacturers to take care of the transport to their warehouses especially during times of instability in international logistics, shipping container shortages and rising shipping prices.

DDP

Due to rising shipping costs and risks to sea travel in the Red Sea, some buyers may ask you to agree on Delivery Duty Paid (DDP). This means you bear all risk and costs as a seller throughout the entire journey of the goods to a nominated destination. The transfer of responsibility for the goods only takes place after final unloading. This means you are also responsible for import duties, taxes and custom clearance in the EU. DDP is the riskiest Incoterm for you as a manufacturer, so watch out!

Tips:

- Check the International Chamber of Commerce’s website for more background information on the different Incoterms.

- Always choose an Incoterm that fits your capabilities and do not take any unnecessary risks. Try to avoid agreements in which you, as an exporter, are responsible for transport and delivery, especially when dealing with first-time buyers. Go for FOB or EXW, since FOB is the most common and will be accepted by most buyers.

4. How to calculate your cost price

To calculate the cost price of an apparel item you need to determine several things:

- What type of costs you are going to make when producing the order.

- How high each cost item will be.

- What profit you want to make.

What type of cost items you need to include in your cost calculation depends on the Incoterm you have agreed on with your buyer. If you provide CM, you will need to include labour and overhead costs in your calculations. CMP also includes packing costs, CMT includes costs for trims. If you provide FOB production, your cost calculation should include all cost items mentioned above, plus material costs.

Table 1: Cost items per Incoterm to include in your cost calculation

| Incoterm | Associated cost items |

| CM | Direct labour costs: costs for labour directly related to production, such as cutting, stitching, quality control. Indirect labour costs: costs for labour indirectly related to production such as management, administration, human resources, sales and sourcing. Overhead costs: costs such as rent, interest, insurance, travel and transport. |

| CMT | Direct labour costs, indirect labour costs, overhead costs plus costs for accessories, labels, hang tags and trims. |

| CMP | Direct labour costs, indirect labour costs, overhead costs plus costs for packing and packaging materials. |

| FOB | Direct labour costs, indirect labour costs, overhead costs plus costs for fabrics and other materials, trims, packing and packaging materials. |

Explanation of the different steps in cost-price calculation

The most common way to calculate costs for most apparel categories is based on the Standard Allowed Minute calculation (SAM). It is also sometimes called ‘Standard Minute Value’. In this study, we use the term SAM. The SAM can be defined as the time it takes to properly produce a certain type of garment. The SAM of a shirt could be around 25 minutes in your factory, for instance. This means it should take an average production line 25 minutes to produce a shirt.

Besides the SAM method of cost calculation, there is also the cost-per-day pricing method. This method is primarily used by volume-focused manufacturers. This report explains both methods but is focused on the SAM method of calculating costs.

In the following paragraphs we calculate the cost price of a shirt made by a fictitious factory in five easy steps. First, we determine how many working minutes the factory has available. Then we determine all the costs the factory has to operate. With this information, we can determine the average cost of one working minute. All that is left to do then is to measure how long it takes to properly produce the shirt. Finally, we can calculate the cost price of the apparel item by multiplying the working minute cost using the SAM.

The role of labour in cost calculation

Before we start our calculation, it is important to understand that calculating costs for a production line that has a lot of manual labour is different from calculating costs for a fully automated factory that has minimal manual labour. The cost calculation for an automated factory is based on the cost of the machines, production time, investments and their returns. This report focuses on a production line in which labour is a substantial cost item.

5. Calculation sheet

If you want to calculate costs yourself, use the cost-price calculation sheet in the annex. Remember: the cost items and numbers that are mentioned below and in the calculation sheet are examples. Always use accurate company data when calculating costs for a real production order.

Step 1: Calculating your factory’s available working minutes

In this report we base our cost-price calculation on a fictitious SME called Best Apparel Manufacturer (BAM). This is a factory with 100 employees, focused on manufacturing shirts. The factory offers CM, so it is only focused on cutting and stitching.

The first step in calculating your cost price is to determine how many minutes your employees can effectively work for you on producing garments. BAM calculates the available minutes based on working days.

| 24 working days per month x 100 employees | 2,400 |

| Daily working hours (8 working hours – 1 hour break) | 7 |

| Monthly available working hours (2,400 x 7) | 16,800 |

| Available working minutes per month (16,800 x 60) | 1,008,000 |

| Available yearly working minutes for 100 employees (1,008,000 x 12 months) | 12,096,000 |

Note that this amount of available working minutes is based on the presumption that every worker works seven hours continuously. However, this is rarely the case on the production floor. Experience shows that around 25% of working time is lost in an efficient factory due to factors like:

- Machine breakdowns

- Delays in cutting

- Reorganisations of the line setup

Step 2: Calculating your factory costs

The second step involves determining the yearly costs of running your factory. Factory costs can be divided into the following categories.

- Direct labour costs include all labour directly related to production, such as cutting, stitching, quality control and packing.

- Indirect labour costs include all labour indirectly related to production, such as management, administration, human resources, sales and sourcing.

- Overhead costs include all costs not related to employees, such as rent, interest, insurance, travel and transport.

For the BAM case, let us presume the following:

| Direct labour costs per year | $300,000 |

| Indirect labour costs per year | $120,000 |

| Overhead costs per year | $50,000 |

| Total working cost | $470,000 |

Step 3: Calculating your factory cost per minute

Now that you have determined your yearly factory costs, the factory cost per minute can be calculated. The working minute cost = (direct labour costs + indirect labour costs + overhead costs) / total production time per year. The working minute cost is the value for one minute of labour that a factory needs to break even (no loss and no profit).

| Direct labour costs per minute $300,000/12,096,000 | $0.025 |

| Indirect labour costs per minute $120,000/12,096,000 | $0.0099 |

| Overhead costs per minute $50,000/12,096,000 | $0.00415 |

| Total break-even cost price for one working minute in BAM factory ($0.025 + $0.0099 + $0.00415) | $0.039 |

Step 4: Determining the SAM for your product

Now that we have calculated how much it costs to run the factory of our company BAM for one minute, it is time to measure how long it takes one employee to produce a particular piece of apparel on average; a shirt in this case. The operation cycle is broken down into operation elements and observed time is captured per element. This exercise can be done by just one employee with a stopwatch and a clipboard. In the case of CM, include the following elements in your time measurement.

- Inspection of fabrics

- Spreading and relaxing of fabric

- Pattern marking

- Cutting

- Transport of panel bundles to the production floor

- Stitching

- Quality control

- Repairs

- Ironing

- Packing

- Finishing

- Final inspection

The time of other activities may have to be included depending on the order, such as washing, printing, embroidering and garment dyeing.

PMTS-software

Larger factories often use ‘PMTS software’ (Principle Member Technical Staff) to help them measure the SAM. This software depends on the information input, such as operator’s hand and body movements.

Popular PMTS programmes to help you calculate your SAM include:

The role of production speed

Production speed significantly affects the final price of your products and your competitiveness. The time employees need to perform specific tasks can vary based on the production line balance, employee experience and motivation. Order quantity significantly affects production line efficiency, with large-volume orders being more efficient to produce than small ones. This increased efficiency is thanks to production lines being more balanced and fewer reorganisations being required for handling fewer orders.

Step 5: Calculating your CM price based on SAM

Let us presume that our BAM factory has measured the SAM for a shirt at 25 minutes.

It is common to include an efficiency percentage of 25% for lost time and a factory profit percentage of 20%. This can differ per factory and order.

| SAM (25 minutes per shirt) x 1.25 efficiency loss | 31.25 |

| Break-even CM price 31.25 SAM x $0,039 minute cost | $1.22 |

| 20% factory profit | $0.24 |

| CM price | $1.46 |

Calculating your CM price based on cost-per-day

As explained at the beginning of this section, there is another way to calculate your CM price. This method is based on cost-per-day. It is primarily used by bigger CM factories that produce large volume orders.

Let us go back to our BAM factory with 100 employees. The total factory costs are determined at $470,000 per year. If we divide the total costs by the number of employees involved in the manufacturing process, then the total cost per worker is: $470,000/100 = $4,700.00 per worker per year.

If one year has 288 working days, this results in $4,700.00/288 = $16.32 per day. This is the price one worker should cost per day to break even.

| Total yearly factory costs | $470,000 |

| Number of employees | 100 |

| Working days per year | 288 |

| Factory costs per day per employee | $16.32 |

Let us presume that a large order has been placed of 12,000 shirts. To produce this order, a production line is needed in which 30 employees work for 25 days to produce the full quantity of shirts. These 25 days include a 25% loss of production efficiency because of issues like setting up the production line, balancing the line and machine breakdowns.

| Case: order of 12,000 shirts at BAM | |

| Employees | 30 |

| Working days | 25 |

| Cost price (30 x 25) x $16.32 | $12,240.00 |

| Profit margin | 20% |

| Total price for the buyer | $14,688.00 |

| Price per piece $14,688.00/12,000 | $1.22 |

Tips:

- As the buyer is responsible for the delivery of the fabrics and trims, it is important that all the materials arrive in the factory according to your planning. Do not forget to mention the consequences if the buyer does not deliver all the materials on time in your contract.

- Do not forget to include the efficiency percentage in your costing.

Calculating CMP orders

In case of CMP orders, note that you need to add the cost for packing materials or trims to the CM price. Let us presume that a shirt is packed as follows:

- One piece in a polybag ($0.02 per polybag)

- 25 pieces in a carton box ($0.10 per carton box)

- 100 pieces in an export carton ($1.00 per export carton box)

To understand the upcharge for the packing materials, we need to calculate the costs per shirt. As there will always be waste involved in packing, include wastage into your calculation (approximately 2%).

| Polybag | $0.02 |

| Inner carton per shirt $0,10/25 | $0.004 |

| Export carton box per shirt $1,00/100 | $0.01 |

| Total packing cost per shirt | $0.034 |

| Wastage 2% | $0.00068 |

| Total packing cost per shirt | $0.03468 |

Tips:

- Do not forget to include finance costs for ordering and purchasing packing materials, if applicable.

- Always try to reduce the environmental impact and financial cost of packaging materials. For example, you can suggest using materials made from recycled cardboard (including hangers) or biodegradable plastics (polybags).

Calculating CMT orders

For CMT orders, you need to include the labels, hang tags and trims in your cost price. Check prices with your trim supplier and add the costs to the CM price of the product before quoting the price to your buyer.

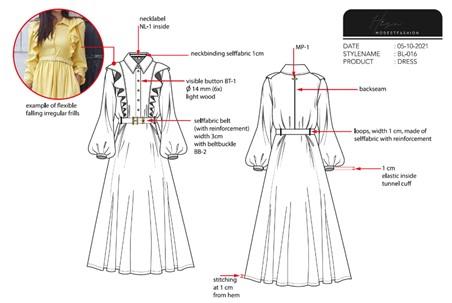

Figure 3: Example of a product design that includes labels and trims

Source: FT Journalistiek

To understand the upcharge for the trims, we need to calculate the costs per shirt. As there will always be waste involved, include wastage into your calculation (approximately 2%).

| Hang tags and labels | $0.10 |

| Interlining | $0.13 |

| Thread | $0.06 |

| Buttons (13) | $0.26 |

| Subtotal | $0.55 |

| Wastage 2% | $0.011 |

| Total trims cost per shirt | $0.56 |

Tips:

- Do not forget to ask about your trim supplier’s minimum order quantity (MOQ) and the upcharge in case the quantity you need does not meet the MOQ.

- Consider cash payments when negotiating prices with your trim suppliers as this can reduce the price.

- Some buyers may require you to source materials trims from a nominated supplier. This can negatively affect your flexibility, cost, speed and liquidity. Always discuss locally available solutions with your buyer to replace nominated suppliers.

- Similar to packing materials, do not forget to include a 2% waste percentage for trims.

- Check this article on Techpacker that explains what should be included in a Bill of Materials (BOM) and how items should be presented.

Calculating FOB orders

FOB means that your buyer does not provide fabrics, trims or packing materials. The factory takes full financial responsibility for sourcing these materials. This can be challenging, as it involves meeting additional buyer requirements. Effective planning is crucial in FOB manufacturing. A delay in obtaining any product element can lead to delays in the entire production process.

An FOB cost calculation includes two cost categories.

- The CM price, covering labour costs.

- All costs related to fabrics, trims, accessories and packing materials are included in the Bill of Materials (BOM).

The Bill of Materials is a complete list of all items that are required to produce a product with corresponding costs and quantities. The BOM helps companies estimate material costs to plan purchases and reduce waste. It also helps you to never miss a single thread, button, zipper or tiny detail when manufacturing your products.

Let us return to the shirt order our BAM factory has calculated. The CM price was $1.46 per shirt. This included an efficiency loss of 25%. In this case:

| CM price per shirt | $1.46 |

| Fabrics (including 3% wastage) | $2.81 |

| Trims (including 2% wastage) | $0.56 |

| Packing (including 2% wastage) | $0.035 |

| Subtotal | $4.86 |

| Factory profit 20% | $0.97 |

| Total FOB price | $5.83 |

About profit margin

Note that this calculation includes an extra FOB profit margin on top of the profit margin that was already included in the calculation of the CM price. This is not a mistake. Factories often include both a CM profit and an FOB profit in their final quotation. This is because CM and FOB are often perceived as different departments with individual profitability responsibilities.

When outsourcing production, it is convenient to include a separate CM profit as the third-party factory will always quote a CM price including profit.

Bear in mind that the 20% profit margin is not fixed. It can vary depending on the buyer, order and company strategy. A buyer who is easy to work with and does not put much pressure on the organisation may be accommodated with a lower profit margin compared to a buyer who has a large number of special requirements and puts more pressure on you. Of course, maximising profit is advisable, but always monitor the relationship between your cost prices and your competitiveness.

Buyer-specific costs

In addition to the CM price and costs related to fabrics, trims, accessories and packing materials, the following buyer-specific costs need to be taken into account in some cases, depending on the agreements you have with your buyer.

- Payment conditions (interest)

- Payment discount

- Chemical testing

- Salesman samples

- DHL packages

- Fit samples

- Finance costs

- Keeping fabric stock

If you want to monitor buyer-specific profitability, it is important to exclude buyer-specific costs from the general costs. This will enable you to measure how profitable individual buyers are and what the impact of a buyer is on your people and organisation, whether it is positive or negative.

Source: FT Journalistiek 2024

Tips:

- When you accept an FOB order, make sure you study the buyer’s requirements in advance, and discuss these with your fabric and trims suppliers.

- Always specify the latest date the buyer should confirm the order to protect yourself from fabric prices rising between the point when you make an offer and when the buyer confirms.

- Do not forget to include wastage. How much wastage is included will depend on the efficiency of your pattern making, cutting, washing and finishing. Include an average of 3-6% for fabrics and 2% for trims and packing.

- Do not forget to check the details of the received order and compare it with your quotation. Some buyers might accidently add details and requirements that were not shared in the calculation phase.

- Do not forget to monitor the currency exchange rate. You need to make sure that an instant increase will be covered in the terms and conditions of your offer.

6. How important is production efficiency?

When considering international competitiveness, most buyers and manufacturers are focused on the minimum wage in a particular country and GSP advantage. GSP stands for ‘Generalised Scheme of Preferences’. It removes import duties from products imported into the EU market from vulnerable developing countries. However, production efficiency often has more influence on FOB prices than minimum wages or import duties.

Efficiency in production can be looked at through different lenses.

- First there is practical efficiency. This refers to moving people and products within a production line setup as little as possible and minimising the time needed to move product between the different production sections.

- Second is line balancing. This refers to a consistent production speed of every worker within the production line so there is a continuous product flow with maximum output.

- Finally, there is personal production speed. This refers to the workers’ motivation to work as fast as possible.

Solving practical efficiency and line balancing issues starts with collecting data in your factory. You do not need to spend a lot on software or machinery. The key to optimising efficiency is to track and monitor every cost item in your factory. This can be done by an employee with a clipboard and pen.

If you want to invest in software and machinery, companies like Juki provide sewing machines that can be digitally linked to a smart factory software system, integrating the cutting and sewing department, and optimising efficiency by balancing the line. Some factories also use QR or barcode tools to measure the time each process or worker takes.

Increasing employee motivation can be a bigger challenge. In many countries, financial rewards are used to boost motivation and productivity. Paying your employees a competitive wage is crucial for keeping them happy. Offering bonuses based on effort and personal results can also help. However, being an attractive employer also means giving employees a sense of pride, recognition and a family feeling. Additionally, providing daycare and health insurance can increase workers’ loyalty to the company.

7. How to determine the right price for your target market?

Before entering any European market, channel or segment, it is important to create a pricing strategy that matches your capacity and sales strategy. To be profitable, you must first understand the level of service your buyer requires.

For instance, if you have a design department and sample room because you mainly work with brands, your overhead costs may be too high to serve large retailers in the lower segment. On the other hand, if you primarily work with high-volume retailers and do not have a design department and sample room, your production efficiency might suffer if you try to meet a brand’s need for flexibility and service.

Some examples of pricing strategies include:

- Cost-plus pricing (no profit optimalisation). Central to this strategy are the costs. Your factory has a fixed profit margin that you want to achieve on all orders. The risk is you may lose sight of market conditions and quote too high or too low.

- Target pricing (top-down, target costing, lean overhead). This strategy focuses solely on what the buyer wants to pay. The risk is you quote too low and make no profit or even a loss.

- Competition-based pricing. This strategy focusses on undercutting competitors. The risk is you quote too low and will make no profit.

- Penetration pricing. Central to this short-term strategy is that you take any order, at any price. The idea is to aggressively gain a market share.

- Portfolio pricing (find a place in the product portfolio). The concept behind this strategy is that you position your factory and product within a certain price range, within a market segment (low, medium or high). This means you will accept orders if they fit into your price range. The risk is that you target a segment that does not fit your capabilities and you forget to include costs that come with high requirements regarding service (in higher market segments), for example.

One good example of an apparel brand that services different market segments within one product category is the German underwear company Schiesser. Their designs are as simple as any competitor’s, but they use high-quality materials, allowing them to charge a higher retail price. On the other hand, the Dutch retailer Zeeman focuses on high volume and market share, targeting the lower price range in the underwear market.

Average retail prices in different EU markets

Your pricing strategy should be based on the type of buyer you want to target and how you want to reel them in. However, some EU countries are richer than others on average, resulting in higher average retail prices for apparel items.

According to Eurostat’s 2023 comparison of retail prices for apparel in Europe, of the top three European importers of apparel, the Netherlands has the highest price level at 106.8 points compared to the European average of 100, followed by France (103.8), and Germany (98.8). Denmark is the EU country with the highest price point (130.7), while Switzerland is the most expensive European country for apparel (144).

Source: Eurostat 2023

Note that brands and retailers that sell in multiple European countries usually keep prices the same or only deviate slightly from the standard retail price.

8. How to reduce your cost price?

To maintain maximum competitiveness, it is important to monitor your expenses and efficiency. Improving your production efficiency is the easiest way to improve profitability. This is also the biggest challenge for many SMEs active in the apparel industry.

Other ways to reduce your costs and increase profitability include:

- Change from CM to FOB

- Expand your sourcing internationally

- Place fabric orders off season

- Minimise stock

- Invest in automation to reduce the number of people in the production line

- Motivate workers to increase production speed

- Reduce your cutting waste

- Sell or re-use your cutting waste.

Tip:

- To reduce labour costs, Turkish apparel manufacturers are increasingly investing in automating their production process. This article in Just Style explains how they are doing this and what the benefits are.

9. How to be competitive

In addition to quality, quantity, sustainability and service level, your pricing is a crucial factor when doing business with European buyers. Most European buyers are experienced in sourcing from various factories in different countries and are typically aware of the price range for specific apparel items of certain qualities and quantities from specific production countries. To stay competitive, you need to be equally knowledgeable about these expectations.

Comparing price level is difficult

Trying to understand the cost level of a different production market is difficult. Data, such as minimum wage, local prices for raw materials and government export support programmes, only say so much.

When comparing your pricing to specific companies, you should also consider factors like production volume and specialisation, the status of the order book, efficiency levels, compliance with environmental regulations, housing costs, and energy and water prices.

Focus on your USPs

Instead of focusing solely on price, a more sensible strategy to become more competitive is to determine your Unique Selling Points (USPs) and advertise them properly. Target buyers that match your capabilities, research them intensively and communicate well. Good quality, competitive pricing and on-time delivery are not USPs. They are non-negotiable requirements that every manufacturer should be able to deliver. Unique selling points are qualities that make you stand out in the crowd. They include:

- Unique designs

- Specials skills and associated machinery

- Flexibility with low minimum order quantities

- Extra-fast delivery

- High service level

- A transparent supply chain

- A good sustainability strategy

Tip:

- Do not focus solely on price. The factory with the lowest FOB price for a certain item of apparel is not always the cheapest factory for a buyer because they might be confronted by delays or quality problems. Ultimately, issues like these can make a factory very expensive even though it seemed cheap initially.

10. What kind of payment terms are acceptable?

For first-time orders, European buyers may give you a down payment via bank transfer (for example, 30%). They will pay the rest once the order has been completed, again via bank transfer. Buyers may also give you a bank guarantee. This statement guarantees that the sum will be paid by a certain date.

Another payment method is the L/C (Letter of Credit). With an L/C, the buyer’s bank must pay the supplier once both parties meet the conditions they have agreed upon. This is the safest payment method for a manufacturer. An L/C can also be used to get finance to purchase materials. However, many buyers no longer use L/C payments because they block cash flow. The administrative costs in case of changes in delivery terms are also high. Be aware that L/C s do not offer financial protection against bankruptcies.

For further orders, most European buyers will ask for a TT (Telegraphic Transfer/Open Account) after 30, 60, 90 or sometimes even 120 days. This means, as a manufacturer, that you finish the production and hand over the shipment and the original documents to the buyer before payment is due. The payment will be made after the number of days that you have agreed on with the buyer. This is a risky payment agreement because you take full financial risk as the manufacturer.

Note that certain production countries confiscate incoming US dollars because the country largely lacks foreign currency reserves. However, not having US dollars makes it difficult for manufacturers to source materials abroad. To work around this, some manufacturers ask their buyers to pay via a third country like Dubai. Hong Kong also used to be popular. This work-around is illegal in some production countries, including Egypt and Ethiopia. Always follow local laws.

Another issue to be aware of when receiving foreign payments is local inflation. If your country faces high inflation and you get paid for your product in US dollars, then you as a manufacturer benefit from the exchange rate. Some European buyers want to keep this benefit for themselves and ask to pay you in your local currency. Be aware of this because a lack of foreign currency can make it very difficult for manufacturers to source materials abroad.

Tips:

- Do not accept payment terms that pose too great a risk for your factory. Be aware that you may not be the only factory that has recently pushed back by asking for safer payment conditions.

- Negotiate payment terms that balance both parties’ interests. For example, consider shorter payment periods or partial payments throughout the production process.

- Build trust. Establishing a trusted relationship with buyers can lead to more favourable payment terms over time. Consistently deliver quality products and maintain transparent communication to foster trust with your buyers.

- Be transparent and share your challenges with the buyer so that they understand the risks involved in doing business.

Further Reading

The CBI report ‘11 Tips for Finding European Buyers’ can help you find interesting prospects and how to approach them.

The CBI study ‘11 Tips for Doing Business with European Buyers’ provides tips on how to successfully approach potential buyers and develop long-lasting business relationships with them.

Frans Tilstra and Giovanni Beatrice for FT Journalistiek carried out this study on behalf of CBI.

Please review our market information disclaimer.

Search

Enter search terms to find market research