Potential for climate-smart coffee from Uganda

Stricter EU legislation has elicited a strong interest of European importers and roasters in sourcing traceable, sustainable coffee, also from Uganda. Interest in sustainably produced coffees does not necessarily translate into higher farmgate prices though, particularly in the mainstream market where price dictates market dynamics. Large coffee traders indicate a willingness to pay premiums for climate-smart attributes, provided that their clients (roasters and brands) are willing to cover the additional costs. However, relatively few voluntarily choose to pay these higher prices.

Rather than pay premiums directly, traders typically invest in sustainability activities at the source, ensuring a supply of climate-friendly coffees, often through a portfolio of certified coffees. While it is true that certification schemes and compulsory premium payment mechanisms lead mainstream roasters to pay some differentials and premiums for climate-friendly coffees, the specifics of these payments are generally not disclosed.

Coffees emphasising carbon reduction are receiving significant interest from European buyers due to the net zero targets set by many large European roasters and retailers. This being a relatively new and evolving area, stakeholders are still navigating how to approach and manage it, especially with regard to who will bear the higher costs associated with these carbon reduction efforts.

On the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), interviewees suggest that EUDR-compliant coffees are expected to fetch higher prices from European buyers, especially those that rely on Robustas from Uganda. The rationale is that premiums are necessary for exporters to recover their investments and efforts to achieve EUDR compliance. As more compliant coffees will be entering the European market over time, the question arises: Will mainstream actors continue to pay premium prices for what becomes the new normal?

Contents of this page

1. Coffee offer in Uganda

Uganda ranked as the world’s sixth-largest coffee producer in coffee marketing year 2023-24, with total coffee production estimated to reach 6.9 million 60-kilogram bags, 85% of which is Robusta. Arabica production in Uganda is expected to amount to approximately 1.0 million 60-kilogram bags.

In recent years, Ugandan coffee exports have experienced rapid growth, with estimates approximating 6.5 million bags for marketing year 2023-24. This positions the country as the fourth-largest exporter globally in terms of volume. The majority of these exports are destined for Italy. The Ugandan government has ambitious plans to further boost exports, aiming to reach 20 million bags of exported coffee annually by 2023, along with a substantial increase in export value.

According to British specialty coffee importer DRWakefield, enhancing the value of Ugandan coffee requires improvements in quality, traceability and the overall reputation of Ugandan coffee. Traceability for Ugandan coffee is currently generally low, mainly because it is predominantly grown by smallholder farmers who sell their coffee to local traders, who then sell it to exporters. The largest share of exported coffee from Uganda is used in regional blends found on supermarket shelves with no traceability.

Most of the coffee in Uganda is of commercial grade (mainstream coffee) and is purchased by local companies of multinational exporters like Ugacof (part of Sucafina), Kyagalanyi Coffee (part of Volcafe), Kawacom (part of Ecom), Olam Uganda, Touton Uganda and Ibero Uganda (part of Neumann Kaffee Gruppe). While most of the Arabica coffee grown in Uganda is also of commercial-grade quality, a relatively small share is classified as specialty coffee.

In recent years, both the national government and private companies like Sucafina and Olam have made substantial investments in the Ugandan coffee sector, and these efforts continue. The focus of these interventions largely revolves around promoting sustainable coffee growing methods and improving quality consistency. This often includes providing farmers with free trainings, seedlings and materials at reduced prices, alongside implementing quality control mechanisms. The results have been quite successful: whereas Ugandan coffee was previously mixed with Tanzanian or Rwandan beans and sold as a blend, it is now increasingly marketed as a single-origin coffee, fetching higher prices.

2. Market interest for Ugandan coffees

Ugandan coffees on the European market

Most major European coffee importers and roasters have Ugandan coffees in their product portfolios. These traders typically purchase large volumes of Robusta of mainstream quality that are commonly used in blends or for processing into instant coffee: the blend offerings of roasters like JDE Peets (Netherlands) and Lavazza (Italy) include Ugandan Robusta, and smaller-scale roasters like Fairtrade Original (Netherlands) incorporate beans from Uganda.

Ugandan Arabica is more commonly sold as single-origin. An increasing number of specialty roasters include Ugandan Arabica in their assortments, like Gardelli (Italy), BirdSong Coffee (Czechia) and Gosling Coffee (Netherlands). Though to a lesser extent, Ugandan Robusta is also marketed as a single-origin product, for example Uganda Kick Espresso of Hanseatic Coffee Roaster (Germany).

What makes coffee from Uganda interesting for European buyers?

Ugandan Robusta coffee is important on the global market due to its high supply volumes and neutral flavour profile. Large-scale (mainstream) roasters typically refrain from purchasing coffees for their blends from countries unable to meet a minimum volume requirement, which makes Uganda a very interesting origin for them.

For actors active in the specialty segment, a common thread among all interviewees was the importance placed on the quality and taste profile of coffees. When quality does not match expectations, an origin becomes less interesting for these types of buyers. However, it is not only quality that matters: specialty coffee buyers aim to find a balance between quality, price affordability, and the need for sustainability, traceability and fair prices.

The interest in Uganda as a specialty coffee destination is fairly recent, given that the country was typically known as a supplier of large volumes of low-quality Robusta beans. For certain European roasters, as indicated by Dutch coffee roaster Gosling Coffee, it is precisely Uganda’s status as a relatively undiscovered origin of specialty coffee that initially piqued their interest. Adding new origins adds value to a roaster’s product portfolio while also contributing to the growing recognition of Uganda’s potential in the specialty coffee market. It must be said, however, that specialty coffees from Uganda are not yet well-perceived by all specialty coffee actors.

Some specialty buyers, like Gosling Coffee, exclusively source Arabica coffee from Uganda, while others are equally interested in the country’s Robusta beans. For instance, Dutch specialty coffee importer The Coffee Quest has a special focus on Robusta due to its significant potential to drive positive change in the region, considering that Robusta accounts for the majority of coffee production in Uganda. Nevertheless, The Coffee Quest also buys Ugandan Arabica, particularly valuing its quality and interesting taste profile.

As highlighted by several interviewees, Uganda presents the interesting opportunity to access high-quality coffee at competitive prices, as it isn’t yet positioned as the most expensive origin. Additionally, some buyers expressed interest in Ugandan coffees due to the country’s robust infrastructure and reliable, efficient logistics system for exports. This is demonstrated by Uganda’s current capacity to export large volumes of coffee. In general, coffee origins offering less consistent supply assurances pose a risk to coffee buyers.

Certain coffee buyers emphasised that their interest in a specific origin increases when they encounter a genuine willingness to collaborate and an openness to establish partnerships based on trust. During the interviews, the majority of buyers noted that, in their view, coffee producers in Uganda are willing to engage in such collaboration. This is precisely why specialised buyers like The Coffee Quest, Gosling Coffee and Wakuli are present in Uganda. All have actively sought to build relationships at origin, implement local sector development initiatives, and work towards a consistent supply of high-quality coffees.

Overall, all interviewees agreed on Uganda’s vast potential to further develop as an attractive coffee origin for the European market, underpinned by its quality offerings, competitive pricing, reliable logistics and opportunities for collaborative partnerships.

Origin trips

Origin trips play an important role in shaping sourcing decisions and fostering partnerships between coffee-producing regions like Uganda and European roasters. For instance, specialty coffee roaster GOTA (Austria) embarked on a trip to Uganda organised by specialty coffee importer Falcon Coffees (UK/Germany). They visited the coffee processor The Coffee Gardens, which collects and buys coffee cherries at a sustainable price from their farmer communities. This experience influenced GOTA’s decision to purchase Ugandan coffees and introduce them to their customers.

Similarly, Dutch roaster Gosling Coffee began sourcing from Uganda after they went on a trip to the country with two other specialty roasters from the UK. Their positive experience during the visit prompted them to start sourcing coffee from Uganda as well. Currently, Uganda accounts for about 45% of all the coffee sourced by Gosling Coffee.

Typically, such origin trips (or buyer missions) encompass various elements aimed at providing insights into the coffee-producing region and its offerings. These trips often include visits to coffee farms and processing facilities, where buyers can observe the cultivation, harvesting and processing techniques firsthand. Potential buyers will meet local producers and cooperatives, and engage in cupping sessions, allowing them to taste a range of coffees from different producers and regions.

Overall, these trips serve as a bridge between a coffee region (and its coffee producers) and European importers/roasters. It facilitates knowledge exchange, helps build partnerships, and leads to informed sourcing decisions that benefit both parties.

Challenges associated with Uganda as a coffee origin

Apart from its positive aspects, Uganda is also recognised as a challenging coffee origin. For smaller-sized players, a notable challenge is the highly competitive buying environment in the region. Large multinational buyers have significant influence due to their size and financial capacity.

Market dynamics have changed, resulting in a stronger contrast between prices paid for high-quality and low-grade coffees. Linking higher quality to better prices has had a significant impact, serving as an incentive for producers to focus on quality improvement and more sustainable production practices. Without such differentiation in prices, coffee producers appear to see little value in investing resources to enhance the quality and sustainability of their crops.

Another identified challenge is the issue of low traceability. As previously mentioned, traceability for Ugandan coffee is generally limited due to the predominant involvement of smallholder farmers that sell their coffee to local traders. Historically, there has not been significant demand for traceable coffees from Uganda, given its role as a supplier of large volumes of commodity-grade coffee. However, this changed with the rise of specialty coffee buyers, who prioritise knowing the origin and story behind the coffee they purchase. Furthermore, the need for traceability has been put on the agenda by the recent European Union Regulation on deforestation-free supply chains (EUDR).

The importance of traceability has received much attention in Uganda. In mid-March 2024, the Uganda Coffee Development Authority (UCDA) announced its commitment to registering all coffee farmers in the National Coffee Registry and implementing a National Traceability System to comply with the European Union regulation. This initiative will assign unique identifiers and geolocations to all coffee farms. The project will be implemented in phases and is estimated to cost up to UGX 35 billion (EUR 8.3 million). An initial commitment of UGX 13 billion (EUR 3.1 million) from the Ministry of Finance was made for the 2024-25 financial year.

What is traceable coffee?

For those interviewed, traceable coffee means knowing the origin of the coffee they purchase. Some also emphasised that traceability includes understanding how their practices impact the community where the coffee grows.

The meaning of ‘knowing the origin of coffee’ varies, and coffees with high traceability in the European market can be traced back to different levels. French specialty coffee importer Belco, for example, offers coffees that can be traced back to either a region, a cooperative, a specific farm, a washing station, or specific microlots.

The level of traceability required varies depending on the buyer’s preference and possibly the coffee’s origin. Take the Austrian roaster GOTA: they buy coffee from the Ugandan Coffee Gardens, a coffee processor representing nearly 600 farming households in Eastern Uganda. Knowing that the coffee comes from Coffee Gardens is enough for GOTA, they do not require individual producer details – even though Coffee Gardens has the capability for full traceability, as they record and tag every incoming cherry batch to an individual farmer for traceability.

Overall, all interviewees agreed that traceability and transparency are very important for European coffee buyers and roasters. They likewise agreed that traceability remains an issue in Uganda, mainly due to the complex internal value chain with numerous middlemen, making it difficult to trace coffee back to the farmers. Also, because most cherries are gathered in a central washing station to wash and process, finding the farmer of a specific batch becomes complicated, requiring the installation of an administrative system that is currently absent.

Close and direct relationships between buyer and producer organisations are seen as a solution to improve traceability: The Coffee Quest emphasises that their strong relationships with farmers help offer traceable coffee. They prioritise developing personal connections with producers, organising visits, and working towards the provision of all the data necessary for their customers. They also acknowledge that this places high expectations on producer organisations, as European buyers request extensive information from producers ranging from sourcing location and environmental impact to the welfare of employees involved in production. Traceability really increases data collection requirements for all actors in the chain.

3. Responsible sourcing practices

Responsible sourcing refers to purchasing coffee in a way that enables economically, socially and environmentally sustainable production, prioritising the wellbeing of producers. This entails adherence to quality, quantity, consistency and transportation standards, along with requirements concerning product origin, traceability, and compliance with a code of conduct or sustainability standard.

In its report Responsible Coffee Sourcing: Towards a Living Income for Producers, the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment categorises responsible sourcing efforts in the coffee industry as follows:

- Specialty coffee companies typically prioritise quality, justifying the payment of higher prices. They often establish direct trade relationships, fostering long-term partnerships between roasters and producers. This segment emphasises pricing transparency to lower dependence on commodity prices.

- Mainstream coffee companies focus more on compliance with their own codes of conduct or certification standards, sometimes resulting in the payment of a small premium. They frequently provide technical support to producers, such as training to increase productivity. This support may target producers within their supply chain or be part of a broader corporate social responsibility programme.

Environmental sustainability is one of the core aspects of responsible sourcing, aiming to preserve resilient ecosystem services and conserve nature. Key environmental issues addressed by industry actors include:

- Prevention of deforestation, a concern given coffee production’s historical impact on forests, exacerbated by climate change. This issue has received much attention since the EUDR was published.

- Implementation of good agricultural practices that minimise water and environmental impacts while supporting biodiversity and soil health. This includes regenerative agriculture and climate-resilient practices.

- Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions linked to coffee production through strategies like using shade trees, reducing chemical inputs and modifying coffee-processing methods. These efforts align with the commitments of roasters and retailers towards net-zero emissions or carbon-neutral coffee, as well as efforts by these companies to use carbon insetting to meet these commitments.

The engagement and interest of coffee buyers in climate-smart agricultural practices are evident. This partly arises out of necessity, as coffee production (and the livelihoods that depend upon it) are threatened by climate change. Industry actors are aware of the urgent need to mitigate climate change and ensure a future where coffee production can survive.

Additionally, the increased focus on sustainability practices is driven by stricter EU sustainability regulations. Many interviewees already had a keen interest in climate-smart practices even before these regulations were implemented. In general, European coffee buyers are actively seeking ways to support coffee-producer organisations without incurring significant costs for them. Since the EU regulations must first be complied with by large buyers, smaller and medium-sized buyers have more time to collaboratively implement these regulatory changes. Thanks to the loyalty built over years of exchange between the interviewed buyers and producers, regulations are seen as challenges to be faced and resolved collectively.

Sustainability projects at origin

Many coffee companies, in both the mainstream and specialty segments, are directly engaged in projects at origin to improve sustainability matters.

Sucafina, the leading trader in Uganda, launched a regenerative agriculture project with Partnerships for Forests in Uganda in 2022. This project aims to help accelerate the transition of the coffee value chain towards regenerative agricultural practices. It focuses on promoting agroforestry, adopting low-carbon farming methods, and fostering sustainable livelihoods for smallholder farmers by ensuring a living income.

Futureproof Coffee Uganda is an origin project aimed at improving sustainable production practices and product quality, led by MVO Netherlands. In this project Dutch companies Wakuli, The Coffee Quest and Fairtrade Original collaborate with Ugandan companies Zombo Coffee Partners, Brand Coffee Farm, Ankole Coffee Producers Cooperative Union (ACPCU) and Uganda Coffee Farmers Alliance (UCFA). The project aims to create a more sustainable coffee chain in Uganda. Primary goals are to establish a sustainable income for local coffee producers while promoting environmentally friendly practices through the adoption of regenerative production models. Additionally, the project focuses on promoting gender equality, diversifying farmers’ incomes and improving coffee quality. To achieve these objectives, each buyer works with their origin partner, organising training sessions and workshops on topics like soil management, agroforestry and gender inclusion.

As highlighted by The Coffee Quest, apart from the positive impact on communities at origin, participating coffee buyers anticipate obtaining consistent and good-quality coffee with a compelling social and environmental impact story attached to it.

4. Climate-smart coffee in Uganda

Climate-smart coffee: what is it?

Climate-smart agriculture, as defined by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), is ‘an approach that helps guide actions to transform agri-food systems towards green and climate-resilient practices. It aims to tackle three main objectives: sustainably increasing agricultural productivity and incomes; adapting and building resilience to climate change; and reducing and/or removing greenhouse gas emissions, where possible’.

It is important to note that while ‘climate-smart’ is a term commonly used by research institutions, public entities and NGOs, it is not widely used in the market by coffee roasters and importers. A quick market scan online did not reveal any instances of coffee roasters or importers marketing the coffee they buy as climate-smart to their consumers.

During the interviews with European roasters and importers, climate-smart coffee was referred to as coffee grown sustainably using regenerative practices, intercropping, agroforestry models, or other farming techniques that enhance ecosystem health. Climate-smart practices may include strategies around soil and water management, good agricultural practices, organic fertilisation and planting trees. There is ambiguity as to what climate-smart coffee exactly means.

The context of climate-smart agriculture in Uganda

Given the wide understanding of what constitutes climate-smart coffee, it is interesting to note that an important share of the coffee grown in Uganda inherently embodies several climate-smart elements. For example, intercropping is a common practice in Uganda as smallholder farms are primarily subsistence-based. Producers typically intercrop coffee with crops like banana, maize, rice, oranges and avocados.

An important share of the additional crops grown on these farms is used for personal consumption, while the rest is cultivated as cash crops to diversify income sources. Some cash crops are targeted at the domestic market, while higher-value crops like vanilla are destined to export markets. The integration of vanilla into intercropping practices is an interesting example, as it was first pioneered by one producer and then adopted by others. This demonstrates willingness to embrace change, integrate new practices, and learn from each other – a trait highly valued by European buyers, as our interviews revealed.

However, it is hard to measure whether these ‘coffee gardens’ or the already-implemented agroforestry models interviewees witnessed during their first visits were the result of programmes executed by nonprofit organisations, government agencies or individual companies, or the direct result of the farmers’ own ancestral techniques. Many farmers have forest-grown coffee, where coffee plants grow naturally rather than being planted. There are also producers who refrain from using chemical fertilisers, largely because many smallholders cannot afford fertilisers or pesticides, resulting in crops that are organic by default.

One company with coffee smart farms in Uganda is The Coffee Gardens, a trader whose mission is defined as ‘By working directly with individual farmers, we can understand their specific needs and ambitions. We work together to improve coffee farming practices using climate-smart and environmentally sustainable approaches’.

Although coffee production in Uganda has climate-smart elements to it, there is still ample room for improvement. For instance, shade tree management currently isn’t a deliberate on-farm management practice among a majority of farmers, and tree pruning has not been emphasised during farmer extension. There are ongoing projects, including those initiated by coffee traders as described above, that focus on enhancing climate-friendly farming practices in the region.

5. Premiums for climate-smart coffees?

The implementation of stricter EU legislation has undoubtedly compelled all stakeholders to adopt more sustainable purchasing practices. Many actors in the coffee sector have prioritised environmental concerns and actively pursue sustainability initiatives. Consequently, sourcing sustainable (climate-smart) coffees has become a top priority for most traders. The industry employs various approaches to pricing and premiums reward producers for their sustainability efforts.

Most common are the payments of premiums for certified coffees, where certification standards include built-in premium price structures. Other actors pay premium prices specifically for higher-quality coffees. Although this can sometimes be linked to climate-smart practices (e.g. coffee farmers using agroforestry techniques typically improve quality by providing shade, slowing cherry maturation and enhancing flavour development), the premiums are paid because the coffee is of higher quality. Sometimes farmers are also rewarded for their carbon sequestration efforts. Instead of getting premiums, producers can also receive benefits in the form of technical support towards transitioning to sustainable farming practices that also aim to boost productivity at the farm level.

The specific practice of paying climate-smart premiums remains uncommon. This is why it’s important that producers of climate-smart coffees not end up paying significantly higher costs, unless these expenses can be clearly linked to producing higher-quality coffee that can fetch higher prices in the market.

Premiums for certified coffee

Most of these schemes offer premiums to producers and producer organisations:

- Organic certification typically includes a premium for producers and exporters, usually around 15-20% higher than conventional coffee prices. The exact premium paid varies by country, producer and buyer, based on quality and negotiation power. To obtain this certification, products must meet standards that include avoiding toxic pesticides, synthetic fertilisers, antibiotics and hormones. These practices are recognised as climate-smart, enhancing efficient water use and soil health.

- Fairtrade includes a wide set of environmental and social requirements. It recently updated its Coffee Standard (in February 2024), requiring certified producers and traders to strengthen deforestation prevention, monitoring and mitigation efforts. The revised Standard is set to become effective in 2026. Fairtrade sets a minimum price structure, which was raised in August 2023. Buyers pay either the Fairtrade Minimum Price for coffee or the market price, whichever is higher. For washed Arabica, the new minimum price is USD 1.80/pound, and for washed Robusta, it is USD 1.25/pound. A premium of USD 0.2/pound is paid on top of that. Fairtrade organic certified coffee has an additional premium of USD 0.40/pound.

- Rainforest Alliance focuses on sustainability and climate resilience in coffee production. This includes promoting the planting of native shade trees, adapting pesticide and fertiliser usage, and planting cover crops between coffee rows. This standard does not guarantee a minimum price or provide a premium for certified coffee. Instead, buyers must pay the Sustainability Differential and Sustainability Investments. The Sustainability Differential is an additional payment to certified producers, rewarding them for sustainable agricultural practices. The Sustainability Investment is a mandatory investment from buyers to help farms comply with sustainability standards. The amounts agreed upon are the result of negotiations between producers and buyers.

- Small Producers’ Symbol (SPP) is a fair trade certification for organised small producers/cooperatives. This standard contributes to climate change mitigation by promoting sustainable production practices and preserving natural areas. It sets a Minimum Sustainable Price, which includes a base price, an organic recognition premium (44 USD/100 pounds) and an SPP incentive (22 USD/100 pounds) for Arabica or Robusta coffee. For washed Arabica, the minimum price is 252 USD/100 pounds, and for washed Robusta, it is 170 USD/100 pounds.

- Common Code for the Coffee Community (4C) prioritises sustainable production of green coffee and post-harvest activities. 4C offers specific add-ons, which are modules that complement the regular certification requirements and procedures. One such module is the 4C Carbon Footprint, designed to measure, reduce and offset emissions throughout the coffee supply chain. Certified coffee producers can claim their coffee as ‘4C Climate Friendly Coffee’. 4C itself does not pay any premium to producers. The final price is defined between buyer and supplier and by the supply-demand situation on a particular market. The price negotiation is geared to calculate production costs and efforts of farmers in compliance with the 4C Climate Friendly certification.

- Some companies also have their own certification schemes, such as Nespresso. The Nespresso AAA Sustainable Quality programme was created in partnership with Rainforest Alliance. Through the AAA Programme, Nespresso works with farmers to improve the yield and quality of their harvests while protecting the environment and improving their livelihoods. To join the programme, a farmer has to produce a specific aroma profile and meet the quality and sustainability requirements. Nespresso pays premium prices and invests in coffee infrastructures and special projects, like those focused on the implementation of agroforestry systems.

The above demonstrates that several certification standards include premium-price structures to compensate producers for meeting sustainability standards in coffee production. While these premiums are important, they should not be the sole focus, especially as they do not necessarily guarantee a better farmer income. Moreover, market volume and uptake also influence profitability and return on investment for certified coffee. To this day, the supply of certified coffee exceeds market demand, resulting in some coffee producers selling their certified coffee as conventional, without receiving any premium prices. Plus, minimum prices and premiums do not consider coffee quality (cupping score), which often adds significant value in the market. Still, some coffee exporters emphasised the importance of certifications as they can validate certain sustainability claims on how coffee is produced and sourced.

Certification in the coffee market – Mainstream vs specialty

Certified coffee is especially found on the mainstream market in Europe. Many large coffee traders, roasters and retailers use third-party certification schemes to work towards their sustainability objectives. By sourcing certified raw material (especially from the main standards: Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, 4C, organic), they show their commitment to and compliance with sustainability. As a result, certification is often a prerequisite for entry to mainstream coffee markets.

JDE Peets, which sources considerable volumes of coffee from Uganda, has set the goal to source 100% ‘responsibly sourced green coffee’ by 2025, meaning coffee that is covered by an independent sustainability verification or certification scheme. Similarly, Ahold Delhaize Coffee Company, the roasting company of retail group Ahold Delhaize (Belgium/Netherlands), ensures that all their coffee is 100% certified, meeting either Rainforest Alliance, fair trade or organic standards.

Specialised coffee buyers tend to have a different approach to certification. The interviewed actors highly value transparency and traceability, more than certification schemes. This is partly because the specialty coffee segment already includes aspects that are characteristic of a sustainable coffee value chain. For instance, the specialty market is strongly linked to practices such as direct trade, close contact between farmers and buyers, traceability systems and price premiums based on coffee bean quality. Certification is therefore often considered counterproductive by specialty buyers, imposing unnecessary costs on farmers.

Buyers in the specialty coffee sector, such as The Coffee Quest, typically prioritise the specific activities and ethos of the producers they collaborate with, rather than solely relying on certifications. However, they also acknowledge that some producers invest significant effort and resources into meeting certification criteria to enhance their product’s value. Since organic certification requires certification throughout the entire supply chain, buyers like The Coffee Quest renew their own certification and that of their warehouse, enabling them to market these certified coffees.

None of this is to say that certifications are never required by specialty buyers themselves. Within the specialty segment, organic certification is a niche market showing particularly strong growth. This is linked to the non-use of pesticides and other synthetic inputs along the organic coffee chain, which is in turn associated with the protection of the environment and human health.

Premiums for high-quality coffee

For many specialty coffee actors, their emphasis on quality is synonymous with a commitment to sustainability. As illustrated by the following, premiums are not necessarily paid specifically for climate-smart coffees; rather, buyers are willing to pay premiums for high-quality coffees that are ideally grown using sustainable production practices.

The synergy between quality and sustainability is evident in the practices of specialty coffee importer Falcon Coffee (UK/Germany). Quality is the primary focus for Falcon Coffee, as improved quality leads to higher household incomes through price premiums. To them, pursuing quality demands training and investment, which leads to the adoption of good agricultural practices, eventually incentivising people to engage in actions that promote better care and management of the environment. The Coffee Gardens, Falcon Coffee’s long-term partner in Uganda, shares the belief that there is a link between a healthy environment, motivated producers, and achieving and maintaining coffee quality.

There is also Dutch roaster Wakuli, whose 2023 impact report highlights a focus on quality improvement, long-term partnerships, fair prices and, since 2023, regenerative coffee production. For Wakuli, paying a higher price for coffee is a direct result of quality improvement as well as the market’s appreciation of that quality. But quality is nothing if the production of coffee is threatened. That is why Wakuli includes a strong focus on regenerative farming in its mission statement. Together with their long-term partners at origin they define what such sustainability projects should entail, such as enhancing water retention and yield, or reducing chemical pesticide and fertiliser use.

Premiums for carbon sequestration

Many large coffee actors in Europe have set net-zero targets. To achieve these goals, many roasters and importers have allocated a separate budget for carbon sequestration efforts, where they focus on reducing their environmental footprint by implementing energy-saving measures, investing in renewable energy sources, and optimising production and packaging efficiency and sustainability. At coffee origins these reduction efforts can translate into investments in climate-resilient coffee varieties, sustainable water management practices, and training programmes, as stated on the website of Ahold Delhaize Coffee Company.

To address the remaining environmental impact, buyers often turn to carbon credits as a form of compensation. Carbon credits involve investing in sustainable development projects that reduce environmental impact elsewhere – a practice known as offsetting.

Carbon offsetting

The carbon offsetting approach can be seen in Uganda through the Acorn project, which is supported by Solidaridad Network and Rabobank. This initiative assists farmers in transitioning to agroforestry practices at scale, enabling smallholder farmers to directly benefit from selling CO₂e from their farms. Acorn offers training and access to the international voluntary carbon market through its platform, allowing any type of actor (from airline company to bank) to purchase credits and offset their impact.

It is very rare for farmers to directly demand premium payments from importers for their carbon credits. Typically, commercial companies handle the sale of carbon credits and subsequently transfer the money to those who sell the credits.

Carbon insetting

Another strategy is carbon insetting, which involves implementing strategies to reduce emissions and carbon footprints within a supply chain. This can include nature-based solutions like reforestation, agroforestry, renewable energy and regenerative agriculture.

This approach is exemplified by the work of Dutch tech startup Carble, which specialises in helping roasters and traders decarbonise their supply chains to meet their net-zero targets. Using proprietary software, Carble gathers carbon storage data from agroforestry coffee farms using satellite imagery and machine learning algorithms. This data helps coffee companies appropriately reward producers for their deforestation-free farming efforts. Based on results, there would be premium payments on farm-gate prices.

While the concept of results-based premium payments has not yet been put into practice, many roasters have committed to carbon reduction efforts through the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), which requires lower emissions. As a result, roasters will most likely find it appealing to purchase products with verified lower carbon levels. This means there is optimism that mainstream buyers will be open to paying potential carbon premiums for such products.

It is important to note that paying future premiums for carbon sequestration is still a new and evolving area. Stakeholders are figuring out how to incorporate this into their sustainability and carbon insetting policies, especially in terms of managing the higher costs associated with these carbon reduction efforts and the question of who will be bearing these costs.

Investments and delivering services

Instead of considering paying out premiums, some industry actors focus on supporting farmers through investments. This can be understood as a Service Delivery Model (SDM): a supply chain structure that offers services like training, access to inputs, and financing to farmers. These models involve coffee producers or producer organisations as recipients of these services, and coffee traders as service providers. These traders are often supported by donors and financial institutions. The aim of this approach is to improve farmers’ performance, leading to increased profitability and improved livelihoods. At the same time, service providers benefit from access to higher volumes and better-quality coffees, along with the opportunity to communicate impact stories from origin.

The approach of Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC) is illustrative. They actively engage in on-the-ground activities and directly invest in supporting farmers’ transition to climate-smart farming methods, often through their Stronger Coffee Initiative. Additionally, they offer services for farmers such as financing and market access. Many of LDC’s investments at the origin level are made in partnership with organisations and financing partners like the Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO) and the Danish International Development Agency (Danida).

Through investments and activities in climate-related projects, LDC can sell climate-friendly coffee to their clients (roasters), assisting them in meeting their sustainability targets, such as carbon reduction. This makes LDC the vehicle through which roasters can claim success in their sustainability efforts. LDC sells large volumes of climate-friendly coffees by offering certified coffees, also compliant with greenhouse gas protocols established by the SBTi.

Although companies like LDC and Neumann Kaffee Gruppe (NKG) suggest that paying a premium for climate-friendly grown coffee is possible, they state this depends on their clients’ (roasters) preferences and their willingness to support payment of these premiums. As traders invest in on-the ground activities, they require their clients’ buy-in to ensure return on their investments. This is why decisions about premium payments are often left to roasters.

Given the strong emphasis on competitive pricing in the mainstream market, the often-limited willingness to pay premiums shouldn’t be surprising. The 2021 study by the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, examining responsible sourcing practices among the world’s largest coffee roasters (including Nestlé, JDE Peet’s, Smucker, Starbucks, Lavazza, Tchibo, Keurig and Costco), clearly concluded that while all these companies have sustainability commitments or projects for producers, none can guarantee a living income for all their producers in their supply chains. All could do more within their sourcing practices to positively influence producer prosperity.

Other considerations about premiums

Traders say it is challenging to negotiate price premiums with their clients, except in cases where premiums are directly tied to higher-quality coffees or certified coffees (those standards that inherently include premiums in their pricing structures). Additionally, some traders believe that demanding premiums for climate-friendly coffees may have a limited lifespan. As sustainability efforts by the industry increasingly adopt climate-friendly farming practices, it may become less feasible to demand premiums for this, given that it could become a standard feature across the market.

Some other concerns shared during the interviews include:

- Determining the recipient of premiums: Should premiums be paid for cherries or green coffee? Since farmers typically sell cherries to cooperatives or washing stations, there is uncertainty about whether cooperatives would pass on premiums to farmers based on the quality of cherries produced.

- Clarifying the purpose of premiums: For specialty coffee buyers it is crucial that their clients (roasters) understand the rationale behind paying premiums. This understanding could influence coffee importers’ willingness to pay a premium price.

- Defining terminology for additional payments: Is it referred to as a premium, or is it simply paying a fair price? Defining the terminology ensures fairness in pricing practices. It helps distinguish between payments that are genuinely meant to incentivise and reward sustainable practices (premiums or differentials) and those that are simply part of a fair market price.

Some stakeholders stated they prefer not to rely on premiums, hoping that farmers will recognise the benefits of climate-smart agriculture themselves. Nevertheless, others also stated that offering a different pricing structure may be necessary to incentivise farmers to invest in producing higher-quality coffees and adopting climate-smart farming practices, even if these changes require initial investments.

6. Climate-smart coffee in the European market

On the marketing side, only some roasters integrate climate-smart practices into their marketing stories. Feedback from interviewees from the specialty segment indicated they do not really see a growing consumer interest in this type of coffee, as quality remains the central driver for consumers. In the case of mainstream coffee, European roasters often rely on certification to communicate their sustainability efforts to customers. They do so in combination with storytelling:

Lavazza’s iTierra! - a climate-smart product linked to certification

iTierra! is Lavazza’s premium coffee range, reflecting ‘the perfect combination of excellence in taste and sustainable cultivation. Through iTierra!, Lavazza communicates its focus on sustainable coffee growing methods that respect the growing communities and the local environment’. Stories are shared on the product package through text and QR codes, as well as on their website and social media outlets.

Lavazza demonstrates its commitment to maintaining long-term supplier relationships by purchasing the coffee used in this range at fair prices, which includes paying sustainability differentials and premiums (adhering to the premium mechanism standards of the certification schemes they use). Each product in the range is organic and/or Rainforest Alliance-certified.

The ¡Tierra! range comprises four products, each aligned with the objectives of the Lavazza Foundation:

- ¡Tierra! Bio-Organic for Planet, a blend dedicated to the project that trains coffee growers on agricultural techniques to manage the effects of climate change;

- ¡Tierra! Bio-Organic for Amazonia, an organic coffee from Peru, where the Foundation is engaged in activities to protect the Amazon rainforest;

- ¡Tierra! Bio-Organic for Cuba, an organic coffee from Cuba, where the Foundation promotes sustainable cultivation methods, promoting the importance of women and young people within the production chain;

- ¡Tierra! Bio-Organic for Africa, an organic coffee grown in East Africa (mainly Uganda), a region where the Foundation supports the new generations of growers by training them on the entrepreneurial management of their activities.

Figure 1: Lavazza’s ¡Tierra! product range

Source: https://sainsburys.co.uk/

Coffees with sustainability stories are also increasingly important in the out-of-home segment, served in places like hotels, offices and airports. Trends in out-of-home segments, like the office space, follow the same path as the general trends in the European coffee sector, and are shaped by changing demographics, a growing awareness of sustainability, and a rising demand for higher-quality coffees.

Some roasters have tapped into this trend: Dutch roaster Gosling Coffee mainly serves the office coffee segment. Based on their experience, companies have shown a desire to cater coffees in their offices that not only provide good quality at reasonable prices but also actively support coffee farmers. Ugandan coffees sell well in this respect.

Other roasters specifically target out-of-home segments with environmentally-friendly coffees. Take the brand Puro Coffee from Belgium: Puro coffee beans come from Fairtrade cooperatives, and are sourced directly from origin. Puro Coffee’s objective is to ensure fair prices for coffee growers and saving the rainforest and its species within coffee-producing countries. They have a number of projects at origin, aim to be carbon-neutral, and source coffees from Uganda. The brand is sold in hospitals, hotels, restaurants, cafés and offices.

Wonder Beans, a brand of Dutch coffee roaster We Wonder Company, sells organic, circular coffee, bought directly from source at a fair price. They cater to both consumers and the business (office) market. The Wonder Beans brand range is broad, from attractively priced to highly unique single-estate specialty coffees. Wonder Beans strives to prevent CO₂ emissions by actively transforming coffee plantations into environmentally friendly farms. The We Wonder Company is active in Uganda too.

Some European coffee importers also focus on offering sustainable coffees to their clients (roasters): Belco, a French specialty coffee and cocoa importer, stands out when it comes to marketing environmentally friendly coffee. For over a decade they have been actively engaged in forest conservation and development through their Forest Coffees® brand. These are high-quality coffees produced in well-preserved environments, without pesticides or fertilisers, recognising the expertise of local farmers in coffee agroforestry techniques. These Forest Coffees® are specialty coffees, organic by nature, and sourced directly from the farm, guaranteeing transparency and traceability. Belco assists their customers in selecting sustainable products by incorporating specific sustainability criteria on their webshop. This enables customers to filter for coffees transported by sail, certified coffees, or those grown in specific types of agroforestry systems.

7. Storytelling: The tool that connects producers and buyers and consumers

Storytelling is a powerful tool. Coffee traders and importers use stories from origin in their communication with roasters, who in turn use those stories to help market their products to consumers. By telling the right story, roasters are able to connect consumers to the coffee’s origin, making coffee consumption a more complete experience.

In this regard, the recent article in SCA News (from the Specialty Coffee Association) is interesting, as it confirms the significant influence of origin information on the sensory perception of professional coffee tasters. ‘For many years, we strived to understand the links between the terroir and coffee [...]; science is finally looking at the other side of the coin, the links between the human mind and the terroir – and we are learning that terroir not only shapes the product but the perception of a product.’

Coffee roaster GOTA noted that, to them and their consumers, well-established origins like Ethiopia – as the birthplace of coffee – require much less storytelling than newer, specialty origins like Uganda. In the case of Uganda, a good story helps market the coffee, and ideally includes elements like smallholder farmers, forest-grown coffees, agroforestry, and other sustainability practices within farms. But, as emphasised by GOTA, coffee quality is most important. If the coffee does not meet customer expectations, storytelling alone will not do much.

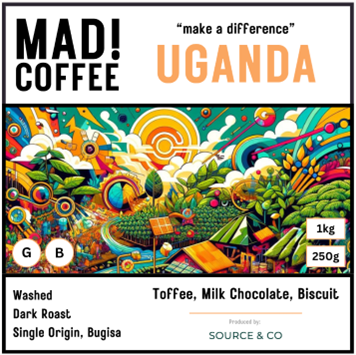

Storytelling is widely used to connect consumers to a product. An interesting case worth mentioning here is Source & Co, a British specialty coffee importer and online retailer. They set the mission to bring the UK closer to the Ugandan communities responsible for sustainable coffee, sharing stories about Ugandan coffee and their climate-smart practices on their website. They describe their Ugandan coffee as follows: ‘With this carbon-neutral coffee from smallholder farmers in Uganda, you can make a difference with each cup and support sustainable development projects in underserved communities.’ This direct message to the consumer not only raises awareness, it is also an invitation to take action.

The Lavazza ¡Tierra! Bio-Organic for the Planet product line is defined as: ‘Climate change represents a real threat to coffee: it might impact the quality of the product and it is the cause of the gradual reduction of cultivated areas. Lavazza ¡Tierra! for Planet is a premium selection of organic Arabica from lands where the Lavazza Foundation is teaching coffee producers agricultural techniques to manage the effect of climate change.’ This message directly addresses the climate crisis, stressing the need for action and linking it to their product.

Roasters are able to share compelling stories about their products thanks to their suppliers, who provide them with the necessary elements and data to articulate their message and/or report on sustainability efforts. As emphasised by large importer LDC, storytelling is an effective strategy for guiding the market towards adopting new standards and practices. By sharing compelling narratives about their sustainability efforts and successes, companies can influence consumer expectations and industry trends. LDC uses storytelling to highlight and showcase their collaborative achievements with partners. ‘At LDC we invest in regenerative practices on the ground, and our clients [roasters] can also claim the benefits of these efforts. This is cross-sharing, and is not considered double accounting because it occurs within the same value chain.’

Storytelling is often employed by companies to highlight their sustainability efforts, for instance those related to regenerative farming practices. As regenerative agriculture includes a wide range of practices aimed at improving soil health and reversing biodiversity loss, it can be challenging for companies to set specific, measurable targets for these practices on a company-wide scale. As noted by Coffee Intelligence, this broad scope allows companies to leverage storytelling to emphasise their commitment to sustainability without necessarily having precise metrics. The lack of well-defined indicators means that companies could more easily manipulate the reporting and assessment of their sustainability efforts, potentially overstating their achievements or masking shortcomings.

This is why Wakuli takes a careful and considerate approach to storytelling, acknowledging it as a critical aspect of their work. Their strategy involves sharing extensive information and communicating about regenerative practices through various channels. They prioritise transparency and traceability without relying on certifications. They also publish an annual impact report. For Wakuli, it is crucial to develop verifiable storylines. This sometimes requires time, which means they are willing to sell coffee from a specific origin without a strong storyline until they find one. This is the case with the Ugandan coffee they purchase from Zombo, with whom they are developing the Regen Agri project.

Storytelling has the power to educate consumers and foster trust and transparency. The Coffee Quest connects storytelling with the power to debunk the stigma surrounding high-quality and eco-friendly Robusta coffee. They share stories on their website and social media accounts on their regenerative agriculture project in Uganda, where they share knowledge on circular production methods with local farmers. Through the stories they share they advocate for the need to push for sustainable Robusta production and Uganda’s potential to lead the way in sustainably-produced Robusta farming, setting a precedent for Robusta producers worldwide.

Figure 2: MAD! Coffee from British specialty importer Source & Co

Source: Source & Co, 2024

Case study 1: Wakuli

Wakuli is a coffee roaster based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. They source their coffee beans directly from small to medium-sized producer organisations in 13 different origins around the world. Their mission is to support farmers in improving their living conditions. As part of this mission, Wakuli has built direct relationships with producer organisations that are actively involved in quality improvement and pay farmers good prices, while they work together with their partners to make coffee production futureproof.

They are deeply committed to promoting regenerative practices in agriculture and actively provide training to assist farmers in transitioning to agroforestry systems. Their strong belief in the potential of regenerative practices to enhance both yield and product quality drives them to also support farmers in securing fair prices for their coffee. In their yearly impact report, they claim: ‘We are fully committed to regenerative coffee production, and we won’t stop until all our coffee is regenerative. Given the urgency, our goal is to achieve this by 2028.’ They also state that this will only be possible if a trustworthy relationship between producers and importers is established and if the market recognises the value of these practices and is willing to pay the price.

Wakuli describes Ugandan coffee as a ‘diamond in the rough’, claiming that the desired quality is not yet there but can be achieved if the region receives proper support. This means the quality that they want to be able to offer is not there yet, but the potential is. At present they work with 50 farmers in the Zombo District, in a collaborative effort between several Dutch organisations and Zombo, their partner in Uganda. The project aims to spread regenerative practices across the region by training farmers in organic fertilisers, composting, and agroforestry systems. This project has been in development for the past three years.

Climate-smart? Wakuli prefers not to use definitions such as ‘climate smart’; they also do not require certifications from their producing partners. Instead, they focus on sustainable production and quality improvement. They state that if the soil quality is improved by applying organic fertilisers and managing a strategic and healthy intercropping system, the yield increases and the benefit becomes palpable for the farmers. Wakuli sees carbon as a side effect of a healthy biodiverse system.

Wakuli’s strategy is to be transparent and offer as much traceability as possible. They communicate their regenerative efforts and provide information to their coffee consumers. And this consumer base is growing: where they started with one coffee shop in Amsterdam, today they offer their coffee directly to consumers at seven establishments in Amsterdam and one in Utrecht.

Case study 2: Gosling Coffee

Gosling Coffee, a roaster based in the Netherlands, describes itself as a supplier of sustainable coffee. They source their coffee beans directly from small-scale farmers in three different origins around the world. Uganda represents around 45% of their entire offer. They roast close to 40 thousand kilograms Ugandan green beans annually. Over the past eight years they have developed trustworthy, traceable and transparent relationships with producers in the two regions they buy from in Uganda: Kasese and Rubirizi.

Gosling’s mission is ‘to provide coffee farmers with a living income and to offer future prospects to current and future generations’. This means they work towards achieving sustainability goals and also execute projects on the ground. They do this together with the producers and supporting organisations. These projects range from collecting school supplies to acquiring humidifiers for washing stations.

Since the start of their relationship with producers in Uganda, Gosling has manifested a firm belief in helping farmers improve their livelihood through sustainable practices. This enduring relationship has facilitated traceability and transparency, easing the conversations about agroecological practices.

Although Gosling feels Ugandan Arabica possesses extraordinary assets, they acknowledge the difficulty of placing it on the specialty coffee market. Still, they successfully tapped into a niche market in Europe for Ugandan coffee by selling it to offices. At one point they supplied Ugandan coffee to the airport.

Given the relatively recent emphasis large corporations have placed on social, environmental and economic impacts, along with their requirements for suppliers to do the same, Gosling strategically entered this market under the premise of ‘good coffee at a good price that makes farmers happy’. So far, Gosling has been successful in matching the market’s needs with the welfare of farmers.

Because Gosling’s mission is to increase farmers’ livelihoods by shortening the value chain and paying farmers a fair price, this relationship has allowed the farmers to steadily increase not only the quality of their product but also of their livelihoods.

Case study 3: Louis Dreyfus Company

Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC) is a trading company involved in the food, feed, fibre and ingredients value chains. It is a global business active in more than 100 countries worldwide. They aim to ‘deliver the right products to the right location, at the right time – safely, responsibly, and reliably’. Their activities span the entire value chain from farm to fork, across a broad range of business lines.

LDC is one of the world’s five largest coffee traders, focusing on commodity-grade coffees. Uganda is of interest to them due to the availability of high-volume, good-quality Robusta suitable for blending and/or processing into soluble coffee.

To them, ‘fairness means working hand in hand with all value chain stakeholders – local farmers, suppliers, partners, customers and consumers – to find shared solutions to common challenges, for the benefit of everyone’. For this reason, they work closely with the supply chain and develop projects directly or through partnerships with organisations with like-minded goals. LDC invests in many sustainability projects on the ground to generate environmental benefits at origin level. The outcomes of these projects are also used by LDC’s clients (e.g. roasters) to help them meet their targets, such as lowering CO2 emissions (insetting in the value chain). Additionally, LDC is willing to pay premiums to producers for their climate-friendly efforts, but only if this aligns with the interest and commitment of their clients.

As part of their sustainability efforts, LDC launched its own sustainability programme in 2022: the Stronger Coffee Initiative. The programme aims to support and empower coffee communities across four key areas: responsible sourcing, farmer support, sustainable operations and sectoral partnerships. Prior to the launch of this programme, LDC was already involved in sustainability projects at origin through its Louis Dreyfus Foundation, which started activities in 2013. In Uganda and Ethiopia, they collaborated with PUR on a project focused on agroforestry and sustainable coffee production, which ran from 2015 to 2022.

LDC declares that climate-smart production practices support farmers while adding value to coffee. Farmers benefit from these practices as they typically help increase yields while reducing the carbon footprint. Agroforestry and other income diversification practices can also support farmers in finding alternative sources of income through byproducts such as fruits and vegetables for internal use or others for commercialisation.

As a company, they are convinced that ‘what nature has to offer is our privilege to use, and we believe that we have a responsibility to use it with great respect, in fairness to all and toward a sustainable tomorrow. This has shaped our purpose’. For this reason, they see their role as a supporter of climate-smart coffee practices and trust this support can lead the entire coffee industry in the future, so that coffee with environmental attributes becomes the norm rather than a niche.

Lisanne Groothuis carried out this study in partnership with Milena Solot of ProFound – Advisers In Development on behalf of CBI.

Search

Enter search terms to find market research